|

WORLD WAR ONE |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

HOME | CASE STUDIES | LAW | NEWS | POLITICS | RIGHTS | SCANDAL | SITE INDEX | WHISTLEBLOWING |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

World War I, also known as the First World War, and (before 1939) the Great War, the War of the Nations, and the War to End All Wars, was a world conflict lasting from August 1914 to the final Armistice (cessation of hostilities) on November 11, 1918. The Allied Powers (led by Britain and France, and, after 1917, the United States) defeated the Central Powers (led by the German Empire, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire), and led to the collapse of four empires and a radical change in the map of Europe. The Allied powers are sometimes referred to as the Triple Entente, and the Central Powers are sometimes referred to as the Triple Alliance.

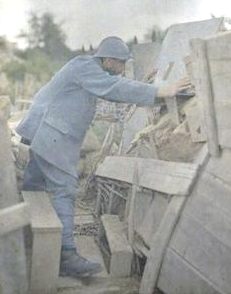

In the trenches: Infantry with gas masks, Ypres, 1917

Introduction

World War I is infamous for the protracted stalemate of trench warfare along the Western Front, embodied within a system of opposing manned trenches and fortifications (separated by a "No man's land") running from the North Sea to the border of Switzerland. Hostilities were also prosecuted, however, by more dynamic invasion and battle, by fighting at sea and - for the first time - in and out from the air. Also, there were some battles that foreshadowed the rapid movement of WWII, take for example the Battle of St. Mihel in 1918. Here, within a matter of one day, American troops, supported by tanks, airplanes, and artillery, advanced over 20 miles, clearing a salient that had been a thorn in the side of the French army since 1914. More than 9 million soldiers died on the various battlefields, and nearly that many more in the participating countries' home fronts on account of food shortages and genocide committed under the cover of various civil wars and internal conflicts. In World War I, only some 5% of the casualties (directly caused by the war) were civilian - in World War II, this figure approached 50%.

Ultimately, World War I created a decisive break with the old world order that had emerged after the Napoleonic Wars, as modified by the mid-19th century national revolutions, the processes of European national unification and European colonialism. Three European land empires were shattered and subsequently dismembered to varying degrees: the German, the Austro-Hungarian and the Russian. In the Balkans and the Middle East, the Ottoman Empire experienced the same fate. Three European imperial dynasties, represented by the Hohenzollern, the Habsburg and the Romanov families in Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia respectively, also fell during the war.

World War I witnessed the first advent of Communism as a means of government in Russia. The following decades would see the transformation of the old Russian Empire into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, a global power. In the east, the demise of the Ottoman Empire paved the way for the states such as Republic of Turkey and a number of successor states and territories throughout the Middle East. In Central Europe, the new states of Czechoslovakia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Yugoslavia were born and Austria, Hungary and Poland were re-created. Shortly after the war, in 1923, Fascists came to power in Italy; in 1933, 14 years after the war, Nazism took over Germany. Problems unresolved or created by the war would be highly important factors in the outbreak, within 20 years, of World War II.

Map of World with Participants in World War I - Allies in green Central Powers in orange - neutral in grey

Causes

On June 28, 1914, Gavrilo Princip, of the Black Hand Gang, assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand while he was visiting Sarajevo. The Archduke was there to assert imperial authority over a disputed province. Though this assassination started the cascade of events that quickly produced war, the causes of the war were multiple and complex. Historians and political scientists have grappled with this question for nearly a century without reaching a consensus. Some of the more prominent explanations are outlined below. For more details see : Causes of World War I

Versailles: Sole guilt of Austria-Hungary and Germany

Early explanations, prominent in the 1920s, stressed the official version of responsibility as described in the Treaty of Versailles and Treaty of Trianon. This alleviated the victors from the consequential guilt of what turned out to be a costly and fruitless bloodbath and was not a baseless accusation; it was Austria, backed by Berlin, that attacked Serbia on July 29 and it was Germany that invaded Belgium on August 3, in accordance with the Schlieffen Plan. Though drastically simplified, such an overview clearly portrays Germany and Austria-Hungary as the aggressors, and therefore, those bearing responsibility. Not surprisingly, this resulted in the humiliation of Germany, which included the demand that Germany pay all the war costs (including pensions) of the Allies. This directly affected the global economy and indirectly contributed to the Great Depression.

The War Guilt clause, or Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, was a major issue in internal German politics in the 1920s and 1930s and worked to the favor of the Nazis, who rode the coattails of German nationalism all the way to the Reichstag. The two became largely indistinguishable. Many prominent British figures, especially economist John Maynard Keynes, rejected the Guilt clause that the French avidly supported. Since 1960, the idea that Germany was primarily responsible was revived by academics such as Fritz Fischer, Imanuel Geiss, Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Wolfgang Mommsen, and V.R. Berghahn. Fischer, for example, emphasized that Germany wanted to control most of Europe or at the very least, unite it through Germany. However, as Fischer points out, diplomatic efforts to do so often centered around Anglo-Germanic cooperation. Likewise, aside from small Germanic territorial enclaves in Belgium, it is unclear exactly what the Germans had to gain in a war, whereas the French and British had territorial and economic-related ambitions, respectively.

Arms Races and Alliances

Another cause of the war was the building of alliances and the related arms race. An example of the latter is the launch of the HMS Dreadnought, a revolutionary battleship that rendered all previous warships obsolete as "pre-dreadnoughts" upon its introduction. Ironically, this weakened Britain's power as a seafaring nation and sparked a major naval arms race in shipbuilding, as the new type of vessel opened up a brand-new chapter in naval warfare, annihilating the old status-quo. The major participants in the race were Britain and Germany, tying in with the concept of new imperialism which gave way to the need for alliances. Overall, nations in the Triple Entente became fearful of the Triple Alliance and vice versa. Paul Kennedy is the historian who has most recently promulgated this thesis.

Plans, Distrust and Mobilization: The First out the Gate Theory

Closely related is the thesis adopted by many political scientists that the war plans of each power automatically escalated the conflict until it was out of control. Fritz Fischer and his followers have emphasized the inherently aggressive nature of Germany's Schlieffen Plan, which outlined how Germany would defend itself in the event of a two front war. If Germany was at war with both France and Russia, it must quickly eliminate one or the other from combat in order to stand a chance at winning the war. Time was of the essence. Due to French fortifications along the border with Germany, the plan called for a violation of Belgium's, and possibly the Netherlands' neutrality. In a greater context, France's own Plan XVII, called for an offensive thrust into the industrial Ruhr Valley that would cripple the German ability to wage war.

Russia's revised Plan XIX implied the mobilization of armies against both Austria-Hungary and Germany. All three created an atmosphere where generals and planning staffs of all the belligerent nations were anxious to capitalize on early offensive maneuvers to seize decisive victories. These military general staffs had elaborate mobilization plans with precise timetables, none more so than Germany, for whom it was decisive to consolidate victory against France before facing the slower-mobilizing Russia. Once the mobilization orders were issued it was understood by both generals and statesman alike that there was little or no possibility of turning back. Furthermore, the problem of communications in 1914 should not be underestimated; all nations still used telegraphy and ambassadors as the main form of communication, resulting in delays from hours to even days.

Militarism and Authoritarianism

President of the United States Woodrow Wilson and many Americans blamed the war on militarism, and this was a theme that figured prominently in anti-German propaganda throughout France, Great Britain and, from 1915 onwards, in the United States. The idea was that the Kaiser Wilhelm II and his autocratic Prussian government had a thirst for military power and glory, and such goals took priority over the needs and wishes of the people. The implication was that a "democratic" government would not have instigated the war, as it was widely proposed that Germany was ultimately responsible. True peace required the abdication of such rulers, the end of the aristocratic system, and consequently, the end of militarism. Wilson fought a "war to end all wars", explaining, "I cannot consent to take part in the negotiation of a peace which does not include freedom of the seas because we are pledged to fight not only to do away with Prussian militarism but with militarism everywhere. Neither could I participate in a settlement which did not include league of nations because peace would be without any guarantee except universal armament which would be intolerable." [October 30, 1918 in Herbert Hoover, Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson p 47] Wilson also acknowledged what he called British and French militarism, hoping his plans for the League of Nations would be able to secure a permanent peace.

Naval supremacy was a goal of Britain and Germany, both following American Admiral Mahan's influential thesis that control of the oceans was vital to a great nation, which therefore had to have a great fleet. In the context of the social-Darwinistic spirit in Germany, economic and military conflict between "races" or nationalities was seen to be inevitable by many military leaders, and the prestige of attaining to or preserving world power was an important consideration for politicians not only for relative international power considerations but domestic satisfaction ones. Germany's decision to increase its navy might is the prime example of this. Not only did increasing naval might serve to channel latent industrial potential into increasing relative power and eroding Britain's hegemony of the seas, the navy served as a national icon which could harness domestic aspirations for "weltmacht" or world power status. However, this led to military rivalry with Britain, which in turn increased its naval might and became less and less favorable toward Germany.

Economic imperialism

Lenin famously asserted that the worldwide system of imperialism was responsible for the war. In this he drew upon the economic theories of English economist John A. Hobson who had earlier predicted the outcome of economic imperialism, or unlimited competition for expanding markets, would lead to a global military conflict in his 1902 book entitled 'Imperialism'[1]. This argument proved persuasive to leftists in the immediate wake of the war and helped explain the popularity of Marxism and Communism among those who suffered most in the conflict. Lenin's 1917 pamphlet "Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism" [2] made the argument, specifically, that large banking interests in the various capitalist-imperialist powers had pulled the strings in the various governments and led them into the war. Related to the idea of economic "shadow forces" working behind the scenes to escalate the conflict, was a thesis, particularly popular in the U.S., that various arms dealers and military industries had led the Great Powers into the war, this is the so-called "Merchants of Death" thesis. However, in the context of the period, it is unclear how these industries had a direct and specific influence on policy-making, and how this sector of the economy was more influential than other industrial and trade sectors, which would presumably be damaged through disrupted trade flows and the loss of markets by a large-scale global war.

Nationalism, Romanticism, Dawn of the "New Era"

The civilian leaders of the European powers found themselves facing a wave of nationalist zeal that had been building across Europe for years, as memories of war faded or were convoluted into a romantic fantasy that resonated in the public conscience. Frantic diplomatic efforts to mediate the Austrian-Serbian quarrel simply became irrelevant, as public opinion (and elite opinion) in key countries demanded war to uphold national honor. Almost all the belligerents envisioned there would be glorious consequences to follow the war. The patriotic enthusiasm, unity and ultimate euphoria that took hold during the "Spirit of 1914" was full of that very optimism regarding the post-war future. (and left a distinct mark on a young Adolf Hitler). Also, the Socialist-Democratic movement had begun to exert pressure on aristocrats throughout Europe, who optimistically hoped a victory would reunite the country.

A Culmination of European History

A localized war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia was almost a given due to Austro-Hungarian Empire's deterriorating world position and the Pan-Slavic, separationist movement in the Balkans, which garnered the support of Slavic elements in Russia, primarily due to Russia's own wishes for a warm water port. Imperial Russia's expansion eastwards is a historical theme that deserves attention - a "threat" only reinforced by the experiences of the Germans in the Napoleonic Wars and Thirty Year's War - where their precarious position in the center of Europe led to the decision for an active defense such as the Schlieffen Plan. France's fury over "losing" the Alsace and Lorraine territories in the Franco-Prussian War gave way to a new word, revanchism, and Germany failed to isolate the French after the League of the Three Emperors fell apart. Overall, the "problems" of 1914 relate directly to problems that are a culmination of historical developments in Europe.

Participants in World War I

The warring parties were divided into two camps:

Opening hostilities

Some of the first hostilities of the war occurred in Africa and in the Pacific Ocean, in the colonies and territories of the European powers. On August 1914 a combined French and British Empire force invaded the German protectorate of Togoland in West Africa. Shortly thereafter, on August 10, German forces based in South-West Africa attacked South Africa, part of the British Empire. Another British Dominion, New Zealand, occupied German Samoa (later Western Samoa) on 30 August; on September 11 the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force landed on the island of Neu Pommern (later New Britain), which formed part of German New Guinea. Within a few months, the Entente forces had driven out or had accepted the surrender of all German forces in the Pacific. Sporadic and fierce fighting, however, continued in Africa for the remainder of the war.

In Europe, the Central Powers — the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire - suffered from mutual miscommunication and lack of intelligence regarding the intentions of each other's army. Germany had originally guaranteed to support Austria-Hungary's invasion of Serbia, but practical interpretation of this idea differed. Austro-Hungarian leaders believed Germany would cover her northern flank against Russia. Germany, however, had planned for Austria-Hungary to focus the majority of its troops on Russia while Germany dealt with France on the Western Front. This confusion forced the Austro-Hungarian army to split its troop concentrations from the south in order to meet the Russians in the north. The Serbian army, coming up from the south of the country, met the Austrian army at the Battle of Cer on 12 August.

Haut-Rhin, France 1917

The Serbians occupied defensive positions against the Austrians. The first attack came on August 16, between parts of the 21st Austro–Hungarian division and parts of the Serbian Combined division. In harsh night-time fighting, the battle ebbed and flowed, until Stepa Stepanovic rallied the Serbian line. Three days later the Austrians retreated across the Danube, having suffered 21,000 casualties as against 16,000 Serbian. This marked the first major Allied victory of the war. The Austrians had not achieved their main goal of eliminating Serbia, and it became increasingly likely that Germany would have to maintain forces on two fronts.

The Schlieffen plan to deal with the Franco-Russian alliance involved delivering a knock-out blow to the French and then turning to deal with the more slowly mobilized Russian army. Rather than invading eastern France directly, German planners deemed it prudent to attack France from the north. To do so, the German army had to march through Belgium. Germany demanded free passage from the Belgian government, promising to treat Belgium as Germany's firm ally if the Belgians agreed. When Belgium refused, Germany invaded and began marching through Belgium anyway, after first invading and securing Luxembourg. It soon encountered resistance before the forts of the Belgian city of Liège, although the army as a whole continued to make rapid progress into France. Britain sent an army to France (the British Expeditionary Force, or BEF), which advanced into Belgium. The first British soldier killed in the war was John Parr, on 21 August 1914, near Mons.

Initially the Germans had great successes in the Battle of the Frontiers (14–24 August 1914). However, the delays brought about by the resistance of the Belgian, French and British forces; the unexpectedly rapid mobilization of the Russians; and overly-ambitious objectives upset the German plans. Russia attacked in East Prussia, diverting German forces intended for the Western Front. Germany defeated Russia in a series of battles collectively known as the Second Battle of Tannenberg (17 August – 2 September).

This diversion exacerbated problems of insufficient speed of advance from railheads, not allowed for by the German General Staff, allowed French and British forces to finally halt the German advance on Paris at the First Battle of the Marne (September 1914) and the Entente forced the Central Powers into fighting a war on two fronts. The German army had fought its way into a good defensive position inside France and had permanently incapacitated 230,000 more French and British troops than it had lost itself in the months of August and September. Yet staff incompetence and leadership timidity, as Ludendorff had needlessly transferred troops from the right to protect Sedan, cost Germany the chance for an early knockout.

Early stages: from romanticism to the Western Front trenches

Hopes and fears

In 1914, the perception of war was romanticized by many people, and its declaration was met with great enthusiasm. The common view on both sides was that it would be a short war of manoeuvre, with a few sharp actions (to "teach the enemy a lesson") and would end with a victorious entry into the enemy capital, then home for a victory parade or two and back to "normal" life. Many thought it would have finished by Christmas of that year. Others, however, regarded the coming war with great pessimism and worry. Some military figures, such as Lord Kitchener and Erich Ludendorff, predicted the war would be a long one. Some political leaders, such as Bethmann Hollweg in Germany, were concerned by the potential social consequences of a war. International bond and financial markets entered severe crises in late July and early August reflecting worry about the financial consequences of war.

The perceived excitement of war captured the imagination of many in the warring nations. Spurred on by propaganda and nationalist fervor, many eagerly joined the ranks in search of adventure. Few were prepared for what they actually encountered at the front.

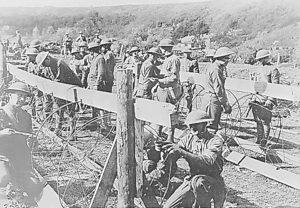

Trench warfare begins

Advances in military technology meant that defensive firepower out-weighed offensive capabilities, making the war particularly murderous, as tactics had failed to keep up. Barbed wire was a significant hindrance to massed infantry advances; artillery, now vastly more lethal than in the 1870s, coupled with machine guns, made crossing open ground a nightmarish prospect. By 1915 both sides were using poison gas. Neither side ever won a battle with gas, but it made life even more miserable in the trenches and became one of the most feared, and longest remembered, horrors of the war.

After the First Battle of the Marne, both Entente and German forces began a series of outflanking manoeuvres to try to force the other to retreat, in the so-called Race to the Sea. Britain and France soon found themselves facing entrenched German positions from Lorraine to Belgium's Flemish coast. Britain and France sought to take the offensive, while Germany defended occupied territories. One consequence was that German trenches were much better constructed than those of their enemy: Anglo-French trenches were only intended to be 'temporary' before their forces broke through German defences. Some hoped to break the stalemate by utilizing science and technology. In April 1915, the Germans used chlorine gas for the first time, opening a four mile wide hole in the Allied lines when French colonial troops retreated before it. This breach was closed by Canadian soldiers at both the Second Battle of Ypres and Third Battle of Ypres, (where over 5000 Canadian soldiers were gassed to death), earning German respect.

Neither side proved able to deliver a decisive blow for the next four years, though protracted German action at Verdun throughout 1916, and the Entente's failure at the Somme, in the summer of 1916, brought the exhausted French army to the brink of collapse. Futile attempts at more frontal assaults, at terrible cost to the French poilu (infantry), led to mutinies which threatened the integrity of the front line, after the Nivelle Offensive in spring of 1917. News of the Russian Revolution gave a new incentive to socialist sentiments among the troops. Red flags were hoisted and the Internationale was sung on several occasions. At the height of the mutiny, 30,000 to 40,000 French soldiers participated.

Canadian troops advanced behind a tank at the Battle of Vimy Ridge One of Canada's greatest military victories

Throughout 1915-17, the British Empire and France suffered many more casualties than Germany, but both sides lost millions of soldiers to injury and disease. Around 800,000 soldiers from the British Empire were on the Western Front at any one time. 1,000 battalions, each occupying a sector of the line from the North Sea to the Orne River, operated on a month-long four-stage rotation system, unless an offensive was underway. The front contained over 6,000 miles of trenches. Each battalion held its sector for around a week before moving back to support lines and then further back to the reserve lines before a week out-of-line, often in the Poperinge or Amiens areas.

In the British-led Battle of Arras during the 1917 campaign, the only military success was the capture of Vimy Ridge by the Canadian Corps under Sir Arthur Currie. It provided the allies with great military advantage and greatly contributed to the identity of Canada. See the Battle of Vimy Ridge for more information

Southern theatres

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers in October–November 1914, due to the secret Turko-German Alliance signed in August 1914, threatening Russia's Caucasian territories and Britain's communications with India and the East via the Suez canal. The British Empire opened another front in the South with the Gallipoli (1915) and Mesopotamian campaigns. In Gallipoli, the Turks were successful in repelling the ANZACs (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps), forcing their eventual withdrawal and evacuation. In Mesopotamia, by contrast, after the disastrous Siege of Kut (1915–16), British Empire forces reorganised and captured Baghdad in March 1917. Further to the west in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, initial British failures were overcome with Jerusalem being captured in December 1917 and the Egyptian Expeditionary Force,under Field Marshall Edmund Allenby, going on to break the Ottoman forces at the Battle of Megiddo in September 1918.

Russian armies generally had the best of it in the Caucasus. Vice-Generalissimo Enver Pasha, supreme commander of the Turkish armed forces, was a very ambitious man, with a dream to conquer central Asia. He was not, however, a practical soldier. He launched an offensive with 100,000 troops against the Russians in the Caucasus in December of 1914. Insisting on a frontal attack against Russian positions in the mountains in the heart of winter, Enver lost 86% of his force at the Battle of Sarikamis. The Russian commander from 1915 to 1916, General Nikolai Yudenich, with a string of victories over the Ottoman forces, drove the Turks out of much of present-day Armenia, and tragically provided a context for the deportation of the Armenian population in eastern Armenia.

In 1917, Russian Grand Duke Nicholas assumed senior control over the Caucasus front. Nicholas tried to have a railway built from Russian Georgia to the conquered territories with a view to bringing up more supplies for a new offensive in 1917. But, in March of 1917 (February in the pre-revolutionary Russian calendar), the Czar was overthrown in the February Revolution and the Russian army began to slowly fall apart.

Italian participation

Italy had been allied to the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires since 1882, but had its own designs against Austrian territory in the Trentino, Istria and Dalmatia, and maintained a secret 1902 understanding with France, effectively nullifying its alliance commitments. Italy refused to join Germany and Austria-Hungary at the beginning of the war, because their alliance was defensive, while Austria had declared war on Serbia. The Austrian government started negotiations to obtain Italian neutrality in exchange for French territories (Tunisia), but Italy joined the Entente by signing the London Pact in April and declaring war on Austria-Hungary in May 1915; it declared war against Germany fifteen months later.

In general, the Italians enjoyed numerical superiority, but were poorly equipped. The Italians went on the offense to achieve their territorial goals. In the Trentino front, the Austro-Hungarian defence took advantage of the elevation of their bases in the mostly mountainous terrain, which was anything but suitable for military offensives. After an initial Austro-Hungaric strategic retreat to better positions, the front remained mostly unchanged, while Austrian Kaiserschützen and Standschützen and Italian Alpini fought bitter close combat battles during summer and tried to survive during winter in the high mountains. The Austro-Hungarians counter-attacked in the Altopiano of Asiago towards Verona and Padua in the spring of 1916 (Strafexpedition), but they also made little progress.

Beginning in 1915, the Italians mounted 11 major offensives on the other front, the Isonzo front (the part of the border north of Trieste), all repelled by the Austro-Hungarians, who had the higher ground. In the summer of 1916, the Italians captured the town of Gorizia. After this minor victory, the front remained practically stable for over one year, despite several Italian offensives, again all on the Isonzo front. In the fall of 1917, thanks to the improving situation on the Eastern front, the Austrians received large reinforcements, including German assault troops. On October 26, they launched a crushing offensive that resulted in the victory of Caporetto: the Italian army was routed, but after retreating more than 100km, it was able to reorganise and hold at the Battle of the Piave River. In 1918, the Austrians repeatedly failed to break the Italian line, and, decisively defeated in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, surrendered to the Entente powers in November.

Throughout the war, Austro-Hungarian Chief of Staff, Conrad von Hötzendorf had a deep hatred for the Italians because he had always perceived them to be the greatest threat to his state. Their betrayal in 1915 enraged him even further. His hatred for Italy blinded him in many ways, and he made many foolish tactical and strategic errors during the campaigns in Italy.

The War in the Balkans

After repelling three Austrian invasions during August-December 1914, Serbia fell to combined invasion by Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Kingdom of Bulgaria, (the latter of which joined the Central Powers in September, 1915) in October 1915. The Serbian army was defeated at Gjilan Kosovo (near the ancient mining city of Novo Brdo), then retreated into Albania and Greece. In late 1915, a Franco-British force landed at Salonica in Greece to offer assistance and to pressure the Greek government into war against the Central Powers. Unfortunately for the Allies, the pro-allied Greek government of Eleftherios Venizelos was dismissed, by the pro-German King Constantine I, before the allied expeditionary force had even arrived. The King then further prevented official Greek entry into the war for two years, until 1917.

Meanwhile, the Salonica Front proved entirely immobile, so much so that it was joked that Salonica was the largest German prisoner of war camp. Only at the very end of the war, after most of the German and Austro-Hungarian troops had been removed, leaving the Front held by the Bulgarians alone, were the Entente powers able to make a breakthrough. This led to Bulgaria's signing an armistice on September 29, 1918.

German trench in swamp area near Mazuric Lakes on the Eastern Front February 1915, before German winter-offensive started in heavy snowstorms

The Eastern Front

Initial Actions

While the Western Front had reached stalemate in the trenches, the war continued in the east. The Russian initial plans for war had called for simultaneous invasions of Austrian Galicia and German East Prussia. Although Russia's initial advance into Galicia was largely successful, they were driven back from East Prussia by the victories of the German generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes in August and September 1914. Russia's less-developed economic and military organization soon proved unequal to the combined might of the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires. In the spring of 1915, the Russians were driven back in Galicia, and, in May, the Central Powers achieved a remarkable breakthrough on Poland's southern fringes, capturing Warsaw on August 5 and forcing the Russians to withdraw from all of Poland, an action known as the "Great Retreat".

The Russian Revolution

Dissatisfaction with the Russian government's conduct of the war grew despite the success of the June 1916 Brusilov offensive in eastern Galicia against the Austrians, when Russian success was undermined by the reluctance of other generals to commit their forces in support of the victorious sector commander. Allied and Russian fortunes revived only temporarily with Romania's entry into the war on August 27: German forces came to the aid of embattled Austrian units in Transylvania, and Bucharest fell to the Central Powers on December 6. Meanwhile, internal unrest grew in Russia, as the Tsar remained out of touch at the front, while Empress Alexandra's increasingly incompetent rule drew protests from all segments of Russian political life, resulting in the murder of Alexandra's favorite Rasputin by conservative noblemen at the end of 1916.

In March 1917, demonstrations in St. Petersburg culminated in the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and the appointment of a weak Provisional Government, which shared power with the socialists of the Petrograd Soviet. This division of power led to confusion and chaos, both on the front and at home, and the army became progressively less able to effectively resist Germany.

The war, and the government, became more and more unpopular, and the discontent led to a rise in popularity of the Bolshevik party, led by Vladimir Lenin, who were able to gain power. The triumph of the Bolsheviks in November was followed in December by an armistice and negotiations with Germany. At first, the Bolsheviks refused to agree to the harsh German terms, but when Germany resumed the war and marched with impunity across Ukraine, the new government acceded to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918, which took Russia out of the war and ceded vast territories, including Finland, the Baltic provinces, Poland and Ukraine to the Central Powers.

After the Russians dropped out of the war, the Entente no longer existed. The Allied powers led a small-scale invasion of Russia. The invasion was made with intent primarily to stop Germany from exploiting Russian resources and, to a lesser extent, to support the Whites in the Russian Revolution. Troops landed in Archangel (see North Russia Campaign) and in Vladivostok.

A carrying party of the Royal Irish Rifles in communications trench - first day on the Somme 1 July 1916

1917-1918

Events of 1917 would prove decisive in ending the war, although their effects would not be fully felt until 1918. The British naval blockade of Germany began to have a serious impact on morale and productivity on the German home-front. In response, in February 1917, the German General Staff (OHL) were able to convince Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg to declare unrestricted submarine warfare, with the goal of starving Britain out of the war. Tonnage sunk rose above 500,000 tons per month from February until July, peaking at 860,000 tons in April. After July, the newly introduced convoy system was extremely effective in neutralizing the U-boat threat. Britain was safe from the threat of starvation.

The decisive victory of Germany at the Battle of Caporetto led to the Allied decision at the Rapallo Conference to form the Supreme Allied Council at Versailles to co-ordinate plans and action. Previously British and French armies had operated under separate command systems.

In December, the Central Powers signed an Armistice with Russia, thereby releasing troops from the eastern front for use in the west. Ironically, German troop transfers could have been greater if their territorial acquisitions had not been so dramatic. With both German reinforcements and new American troops pouring into the Western Front, the final outcome of the war was to be decided in that front. The Central Powers knew that they could not win a protracted war now that American forces were certain to be arriving in increasing numbers, but held high hopes for a rapid offensive in the West, using their reinforced troops and new infantry tactics. Furthermore, the rulers of both the Central Powers and the Allies became more fearful of the threat first raised by Ivan Bloch in 1899, that protracted industrialized war threatened social collapse and revolution throughout Europe. Both sides urgently sought a decisive, rapid victory on the Western Front as they were both fearful of collapse or stalemate.

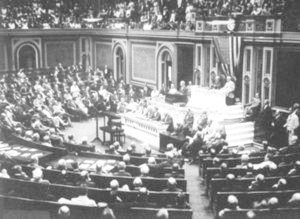

President Wilson before Congress announcing break in relations with Germany February 3, 1917

Entry of the United States

America's policy of insisting on neutral rights while also trying to broker a peace resulted in tensions with both Berlin and London. US president Woodrow Wilson repeatedly warned that he would not tolerate unrestricted submarine warfare, and the Germans repeatedly promised to stop. In January 1917 the German military decided that unrestricted submarine warfare was the best gamble to choke British supplies before the American troops could arrive in large numbers. A proposal to Mexico to join the war was exposed in February, bringing war closer.

After further U-boat attacks on American merchant ships, Wilson requested that Congress declare war on Germany, which it did on April 6, 1917. The House approved the war resolution 373-50, the Senate 82-6, with opposition coming mostly from German American districts. Wilson hoped war could be avoided with Austria-Hungary; however, when it kept its loyalty to Germany, the US declared war on Austria-Hungary in December 1917.

Although the American contribution to the war was important, particularly in terms of the threat posed by an increasing US infantry presence in Europe, the United States was never formally a member of the Allies, but an "Associated Power." Significant numbers of fresh American troops only arrived in Europe in the summer of 1918, when they started arriving at 10,000 a day.

Germany miscalculated that it would be many more months before large numbers of American troops could be sent to Europe, and that, in any event, the U-boat offensive would prevent their arrival.

The United States Navy sent a battleship group to Scapa Flow to join with the British Grand Fleet, a number of destroyers to Queenstown, Ireland and several submarines to the Azores and to Bantry Bay, Ireland to help guard convoys. Several regiments of U.S. Marines were also dispatched to France. However, it would be some time before the United States would be able to contribute significant manpower to the Western and Italian fronts.

The British and French wanted the United States to send its infantry to reinforce their troops already on the battlelines, and not use scarce shipping to bring over supplies. Thus the Americans primarily used British and French artillery, airplanes and tanks. However, General John J. Pershing, American Expeditionary Force (AEF) commander, refused to break up American units to be used as reinforcements for British Empire and French units (though he did allow African American combat units to be used by the French). Pershing ordered the use of frontal assaults, which had been discarded by that time by British Empire and French commanders as too costly in lives of their troops. To the astonishment of the Allies, the dispirited Germans broke and ran when the Americans came running, and the AEF suffered the lowest casualty rate of any army on the Western Front. (Most of its deaths were due to disease.)

|

WE ACCEPT NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE ACCURACY OF ANY FEATURED LINKS

IF YOU HAVE ANY GOOD STORIES TO TELL WE'D LIKE TO HEAR FROM YOU. WHY NOT BUILD A WEBSITE OF YOUR OWN TO TELL OF PROBLEMS IN YOUR AREA - IT'S YOUR RIGHT. WE WILL LINK TO YOUR SITE WITH A SHORT SUMMARY.

With thanks to Action Groups around the world for the supply of real case history and supporting documents.