|

Making

a borehole using a wire pulley and weight system, that is powered by a

diesel engine. The water table was confirmed here on site as being 4

meters from the surface, meaning that this land shares the water with

Herstmonceux Museum. The immediate worry is that with 70 households all

creating garden waste, and all flushing toilets and washing water down

newly installed drains, that leakage into the water table is bound to

contaminate that water for well users.

WATER

CONTAMINATION

Concerns

have been raised that placing a housing estate over land that is the

source of water for Herstmonceux Museum, could contaminate their water

supply. Herstmonceux Museum is not connected to the mains, so relies on

an ancient well for drinking and washing water. Similar issue has been

raised by other residents in Chapel Row, who also have wells is their

gardens.

WATER

CONTAMINATION - If houses are built on the hill that supplies the last

surviving well in Herstmonceux, all of those who presently enjoy a

sustainable water supply are likely to be poisoned by pesticides from a

number of the

gardens of the proposed housing - at the moment that looks like being 28

units positioned directly above and in the groundwater soakage line of fire. In addition, where the hard standings of

the proposed 70 houses are to be gully drained to a point lower than the

twin wells, rainwater soakage that supplies the wells will be diverted away

potentially starving the wells of water, save that from the garden areas

that are impossible to gully.

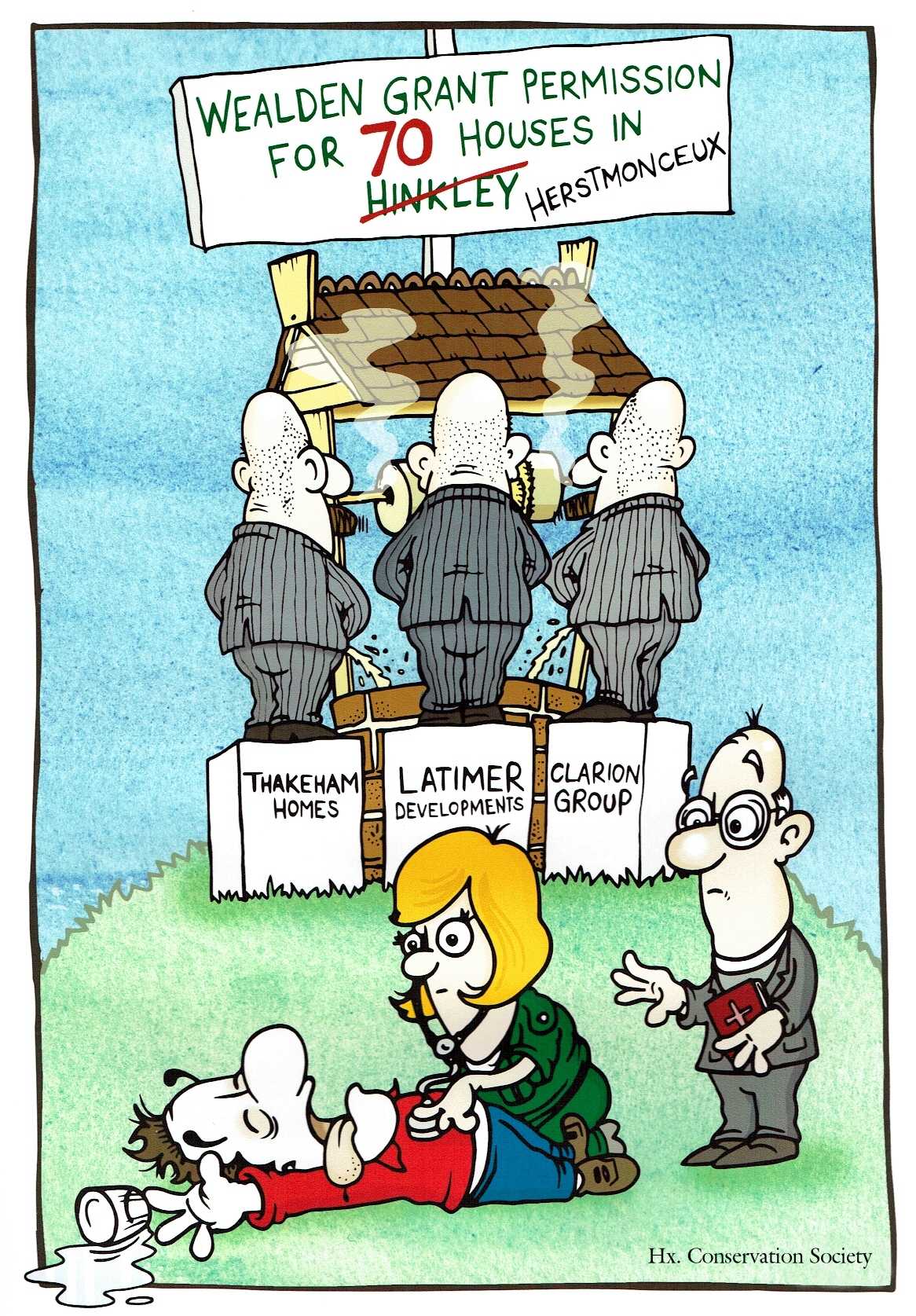

The amusing cartoon above portrays the situation that perhaps the

developers were not aware of, when they bought into a situation that they

should have been able to rely on.

Unfortunately, the council concerned and

the advisers to the original applicants appear to have been less diligent

than they might have been in the rush to profit from a windfall situation.

The question that is probably on your lips is: "Was that an

oversight, or was it deliberate"?

After

each borehole is hammered out, a steel cap is concreted in place and

numbered. Note the padlocks to prevent accidental access from passers by

and nosey animals. These boreholes will be monitored over the coming

weeks. If contamination is found, it is unlikely that houses could be

built on this site.

WELL

RECONSTRUCTION - SUSSEX ENGLAND JUNE 2013

The well at Herstmonceux Museum in Sussex was rediscovered in 1982, and although

put back into use immediately, for the last fifteen years all that had

been done to preserve it was the rebuilding of the brick head and the making of a

wooden hatch cover - to

among other things prevent people and objects falling in.

In

June of 2013 a draughtsman got to work designing a traditional frame;

producing the drawings from which a craftsman could work to. They went through

several gestations until finally the scale seemed right in the context

of an estate that dated from C. 1800.

Restoration

in progress June 2013 - A well head at Herstmonceux Museum, Sussex, England.

The

bell for this well is dated 1898. During the re-build some slight modifications

were necessary to the timber framework. The height was raised by 3"

and the roof was lengthened. The 6" timber uprights were slotted

into the base timbers with a hand cut mortise and tenon joint

3"x3" using chisels and drills as seen below.

Restful

view of the Sussex countryside at Herstmonceux - an area of outstanding

natural beauty (AONB), and an iconic 'Roman' silhouette of the well roof taking

shape as seen from the courtyard below. Herstmonceux Museum was

listed on an English Heritage Monument Protection Programme from 2003.

The Trust that manages this site get no help from English Heritage or

the National Lottery towards the considerable cost of restorations. This

is the only working well in the village - used daily for water supplies.

it has been in use since before Augustus Hare lived in Lime Park (C.

1830).

Detail

picture of the base triangulating support timbers. These are important

to stabilise the structure in high winds.

Similar cross bracing is used to support the longitudinal roof timbers,

known as purlins when used in the roof of a house - you can see the roof

cross bracing in the pictures below.

Four

timbers supporting the ridge beam, two more to go. The well is taking

shape. The ridge beam was raised a further 6" over and above that

raised already, another incremental improvement

on the original drawings above, to increase clearance for the well bell.

If you need a well head built, the builder of this structure will be

pleased to suggest a design and quote for the construction for your

dream house. This well feeds a raised storage tank via a three stage

single phase pump. The pump is controlled via a bespoke magnetic sensor,

in turn feeding from a float, made from an old soda-pop bottle attached

to a thin stainless-steel wire arm (316 grade welding rod). The magnetic

sensor switches a Maplin solenoid operated relay to amplify the signal

for 240 volt switching. Simples

To

complete this restoration we need to fit a bell dating from 1898. The

bearing carriers are bolted to the beams supporting the bell. The

yoke has been treated with preservative against woodworm, wet & dry

rot. The ironwork has been oiled and painted with two coats of black and

the oak yoke has been varnished. Rather than polish the bell, we thought

we'd simply clean her up and give her a protective coat of lacquer that

could easily be removed without damaging the bronze, should the need

ever arise. The bell is after all an antique.

Once

the workings are installed and operable, the roofing proceeds with

fitting of treated battens. The well head looks a bit like a

mini-house. The roof will most probably have tiles (or slates)

eventually. For now though we are going to recycle some of the

corrugated iron that had been used to clad the generating buildings

during World War

II.

She's

starting to look like something, blending into the Sussex scenery as if

she'd never gone. We are looking forward to fitting the well wheel as

time allows. We will

treat all of the timber frame eventually, even though the new timbers

are tanalised. This structure is going to last another 150 years.

Walkers from the village (Jubilee Walk) have been commenting on the work done so far.

Very encouraging.

Water

is essential to life, for drinking, washing and heating. We take it for

granted in developed countries, but then you should try surviving from a

water hole. Try raising water by hand using buckets and rope, just

as millions of people still do in undeveloped lands.

It's

still done like this in countries all over the world

WATER

FOR LIFE - A BRIEF HISTORY OF WELLS

A water well is an excavation or structure created in the ground by digging, driving, boring, or drilling to access groundwater in underground aquifers. The well water is drawn by a pump, or using containers, such as buckets, that are raised mechanically or by hand.

Well, that was in days gone by. These days an electric pump linked to a

float switch does the job.

Wells can vary greatly in depth, water volume, and water quality. Well water typically contains more minerals in solution than surface water and may require treatment to soften the water.

A

very old well head - Galle, Sri Lanka

OLDEST WELLS

The world's oldest known wells, located in Cyprus, date to 7500 BC. Two wells from the Neolithic period, around 6500 BC, have been discovered in Israel. One is in Atlit, on the northern coast of

Israel, and the other is the Jezreel Valley.

Wood-lined wells are known from the early Neolithic Linear Pottery culture, for example in Kückhoven (an outlying centre of Erkelenz), dated 5090 BC and Eythra, dated 5200 BC in Schletz (an outlying centre of Asparn an der Zaya) in Austria.

Australian Aborigines relied on wells to survive the harsh Australian desert. They would dig down, scooping out sand and mud to reach clean water, then cover the source with spinifex to prevent spoilage. Non-Aborigines call these native wells, soaks or soakages.

Stepwells are common in the west of India. In these wells, the water may be reached by descending a set of steps. They may be covered and are often of architectural significance. Many stepwells were also used for leisure, providing relief from the daytime heat.

The

above are more fine examples of traditional well-heads from around the

world.

QANATS

A qanat is an ancient water collection system made up of a series of wells and linked underground water channels that collects flowing water from a source usually a distance away, stores it, and then brings the water to the surface using gravity. Much of the population of Iran and other arid countries in Asia and North Africa historically depended upon the water from qanats; the areas of population corresponded closely to the areas where qanats are possible.

In Egypt, shadoofs and sakiehs are used. When compared to each other however, the Sakkieh is much more efficient, as it can bring up water from a depth of 10 metres (versus the 3 metres of the shadoof). The Sakieh is the Egyptian version of the

Noria.

From the Iron Age onwards, wells are common archaeological features, both with wooden shafts and shaft linings made from wickerwork.

Lime

Cross, Herstmonceux March 2015 - Surveyors make another borehole. The

water table was again confirmed here on site as being 4 meters from the

surface, meaning that this area of land also shares the water with

Herstmonceux Museum. It seems from this that any houses built here are

bound to cause long term contamination to the water table. Imagine a

leak from the soil system into the water table. How would that affect

those locally that depend on water from wells?

DUG WELLS

Until recent centuries, all artificial wells were pumpless hand-dug wells of varying degrees of formality, and they remain a very important source of potable water in some rural developing areas where they are routinely dug and used today. Their indispensability has produced a number of literary references, literal and figurative, to them, including the Christian Bible story of Jesus meeting a woman at Jacob's well (John 4:6) and the "Ding Dong Bell" nursery rhyme about a cat in a well.

Hand-dug wells are excavations with diameters large enough to accommodate one or more persons with shovels digging down to below the water table. They can be lined with laid stones or brick; extending this lining upwards above the ground surface to form a wall around the well serves to reduce both contamination and injuries by falling into the well. A more modern method called caissoning uses reinforced concrete or plain concrete pre-cast well rings that are lowered into the hole. A well-digging team digs under a cutting ring and the well column slowly sinks into the aquifer, whilst protecting the team from collapse of the well bore.

Hand dug wells provide a cheap and low-tech solution to accessing groundwater in rural locations in developing countries, and may be built with a high degree of community participation, or by local entrepreneurs who specialize in hand-dug wells. They have been successfully excavated to 60 metres (200 ft). Hand dug wells are inexpensive and low tech (compared to drilling) as they use mostly hand labour for construction. They have low operational and maintenance costs, in part because water can be extracted by hand bailing, without a pump. The water is often coming from an aquifer or groundwater, and can be easily deepened, which may be necessary if the ground water level drops, by telescoping the lining further down into the aquifer. The yield of existing hand dug wells may be improved by deepening or introducing vertical tunnels or perforated pipes.

Drawbacks to hand-dug wells are numerous. It can be impractical to hand dig wells in areas where hard rock is present, and they can be time-consuming to dig and line even in favourable areas. Because they exploit shallow aquifers, the well may be susceptible to yield fluctuations and possible contamination from surface water, including sewage. Hand dug well construction generally requires the use of a well trained construction team, and the capital investment for equipment such as concrete ring moulds, heavy lifting equipment, well shaft formwork, motorized de-watering pumps, and fuel can be large for people in developing countries. Construction of hand dug wells can be dangerous due to collapse of the well bore, falling objects and asphyxiation, including from

dewatering

pump exhaust fumes.

Woodingdean well, hand-dug between 1858 and 1862, is claimed to be the world's deepest hand-dug well at 1,285 feet (392 m). The Big Well in Greensburg, Kansas is billed as the world's largest hand-dug well, at 109 feet (33 m) deep and 32 feet (9.8 m) in diameter. However, the Well of Joseph in the Cairo Citadel at 280 feet (85 m) deep and the Pozzo di S. Patrizio (St. Patrick's Well) built in 1527 in Orvieto, Italy, at 61 metres (200 ft) deep by 13 metres (43 ft) wide are both larger by volume.

Well,

well, well - types of well

DRILLED WELLS

Drilled wells are typically created using either top-head rotary style, table rotary, or cable tool drilling machines, all of which use drilling stems that are turned to create a cutting action in the formation, hence the term 'drilling'.

Drilled wells can be excavated by simple hand drilling methods (augering, sludging, jetting, driving, hand percussion) or machine drilling (rotary, percussion, down the hole hammer). Deeprock rotary drilling method is most common. Rotary can be used in 90% for formation types.

Drilled wells can get water from a much deeper level than dug wells can - often up to several hundred metres.

Drilled wells with electric pumps are used throughout the world, typically in rural or sparsely populated areas, though many urban areas are supplied partly by municipal wells. Most shallow well drilling machines are mounted on large trucks, trailers, or tracked vehicle carriages. Water wells typically range from 3 to 18 metres (9.8–59 ft) deep, but in some areas can go deeper than 900 metres (3,000 ft).

Rotary drilling machines use a segmented steel drilling string, typically made up of 6 metres (20 ft) sections of galvanized steel tubing that are threaded together, with a bit or other drilling device at the bottom end. Some rotary drilling machines are designed to install (by driving or drilling) a

steel casing into the well in conjunction with the drilling of the actual bore hole. Air and/or water is used as a circulation fluid to displace cuttings and cool bits during the drilling. Another form of rotary style drilling, termed 'mud rotary', makes use of a specially made mud, or drilling fluid, which is constantly being altered during the drill so that it can consistently create enough hydraulic pressure to hold the side walls of the bore hole open, regardless of the presence of a casing in the well. Typically, boreholes drilled into solid rock are not cased until after the drilling process is completed, regardless of the machinery used.

The oldest form of drilling machinery is the cable tool, still used today. Specifically designed to raise and lower a bit into the bore hole, the 'spudding' of the drill causes the bit to be raised and dropped onto the bottom of the hole, and the design of the cable causes the bit to twist at approximately ¼ revolution per drop, thereby creating a drilling action. Unlike rotary drilling, cable tool drilling requires the drilling action to be stopped so that the bore hole can be bailed or emptied of drilled cuttings.

Drilled wells are usually cased with a factory-made pipe, typically steel (in air rotary or cable tool drilling) or plastic/PVC (in mud rotary wells, also present in wells drilled into solid rock). The casing is constructed by welding, either chemically or thermally, segments of casing together. If the casing is installed during the drilling, most drills will drive the casing into the ground as the bore hole advances, while some newer machines will actually allow for the casing to be rotated and drilled into the formation in a similar manner as the bit advancing just below. PVC or plastic is typically welded and then lowered into the drilled well, vertically stacked with their ends nested and either glued or splined together. The sections of casing are usually 6 metres (20 ft) or more in length,

and

6

to 12 in (15 to 30 cm) in diameter, depending on the intended use of the well and local groundwater conditions.

Surface contamination of wells in the United States is typically controlled by the use of a 'surface seal'. A large hole is drilled to a predetermined depth or to a confining formation (clay or bedrock, for example), and then a smaller hole for the well is completed from that point forward. The well is typically cased from the surface down into the smaller hole with a casing that is the same diameter as that hole. The annular space between the large bore hole and the smaller casing is filled with bentonite clay, concrete, or other sealant material. This creates an impermeable seal from the surface to the next confining layer that keeps contaminants from traveling down the outer sidewalls of the casing or borehole and into the aquifer. In addition, wells are typically capped with either an engineered well cap or seal that vents air through a screen into the well, but keeps insects, small animals, and unauthorized persons from accessing the well.

At the bottom of wells, based on formation, a screening device, filter pack, slotted casing, or open bore hole is left to allow the flow of water into the well. Constructed screens are typically used in unconsolidated formations (sands, gravels, etc.), allowing water and a percentage of the formation to pass through the screen. Allowing some material to pass through creates a large area filter out of the rest of the formation, as the amount of material present to pass into the well slowly decreases and is removed from the well. Rock wells are typically cased with a PVC liner/casing and screen or slotted casing at the bottom, this is mostly present just to keep rocks from entering the pump assembly. Some wells utilize a 'filter pack' method, where an undersized screen or slotted casing is placed inside the well and a filter medium is packed around the screen, between the screen and the borehole or casing. This allows the water to be filtered of unwanted materials before entering the well and pumping zone.

Water

holes from around the world: India, Afghanistan & Africa - we all need water to survive, a basic

ingredient of human life. The methods are different, so are the container materials, but the need is as old as time itself.

|