|

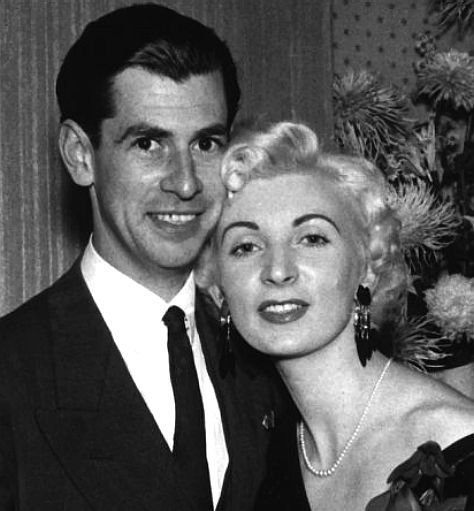

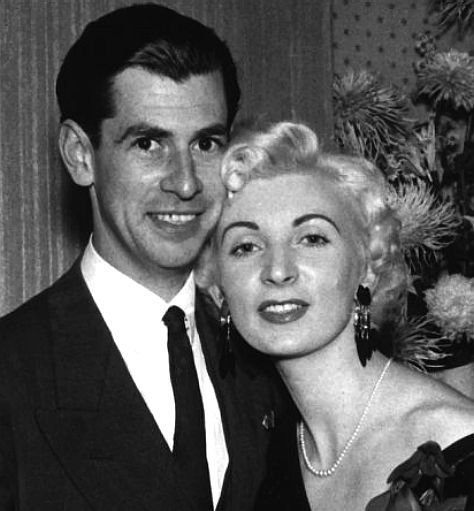

David

Blakely and Ruth Ellis - Cullen and Ruth Ellis

Ruth Ellis (9 October 1926—13 July 1955) was the last woman to be executed in the United Kingdom, after being convicted of the murder of her lover, David Blakely.

From a humble background, Ellis was drawn into the world of London nightclub hostessing, which led to a chaotic life of brief relationships, some of them with upper-class nightclubbers and celebrities. Two of these were Blakely, a racing driver already engaged to another woman, and Desmond Cussen, a retail company director.

On Easter Sunday 1955, Ellis shot Blakely dead outside the Magdala public house in Hampstead, and immediately gave herself up to the police. At her trial, she took full responsibility for the murder and her courtesy and composure, both in court and in the cells, was noted in the press. She was hanged at Holloway Prison, London, by Albert Pierrepoint.

Ellis was born in the Welsh seaside town of Rhyl, the third of six children. During her childhood her family moved to Basingstoke. Her mother, Elisaberta (Bertha) Cothals, was a Belgian refugee; her father, Arthur Hornby, was a cellist from Manchester who spent much of his time playing on Atlantic cruise liners. Arthur changed his surname to Neilson after the birth of Ruth's elder sister Muriel.

Ellis attended Fairfields Senior Girls' School in Basingstoke, leaving when she was 14 to work as a waitress. Shortly afterwards, in 1941 at the height of the Blitz, the Neilsons moved to London. In 1944, 17-year-old Ruth became pregnant by a married Canadian soldier named Clare and gave birth to a son, who she named Clare Andrea Neilson, known as "Andy". The father sent money for about a year, then stopped. The child eventually went to live with Ellis's mother.

RUTH'S CAREER

Ellis became a nightclub hostess through nude modelling work, which paid significantly more than the various factory and clerical jobs she had held since leaving school. Morris Conley, the manager of the Court Club in Duke Street, where she worked, blackmailed his hostess employees into sleeping with him. Early in 1950 she became pregnant by one of her regular customers, having taken up prostitution. She had this pregnancy terminated (illegally) in the third month and returned to work as soon as she could.

On 8 November 1950, she married 41-year-old George Ellis, a divorced dentist with two sons, at the register office in Tonbridge, Kent. He had been a customer at the Court Club. He was a violent alcoholic, jealous and possessive, and the marriage deteriorated rapidly because he was convinced she was having an affair. Ruth left him several times but always returned.

In 1951, while four months pregnant, Ruth appeared, uncredited, as a beauty queen in the Rank film Lady Godiva Rides Again. She subsequently gave birth to a daughter Georgina, but George refused to acknowledge paternity and they separated shortly afterwards. Ruth and her daughter moved in with her parents and she went back to hostessing to make ends meet.

MURDER SHE WROTE

In 1953, Ruth Ellis became the manager of a nightclub. At this time, she was lavished with expensive gifts by admirers, and had a number of celebrity friends. She met David Blakely, three years her junior, through racing driver Mike Hawthorn. Blakely was a well-mannered former public school boy, but also a hard-drinking racer. Within weeks he moved into her flat above the club, despite being engaged to another woman, Mary Dawson. Ellis became pregnant for the fourth time but aborted the child, feeling she could not reciprocate the level of commitment shown by Blakely towards their relationship.

She then began seeing Desmond Cussen. Born in 1921 in Surrey, he had been an

RAF pilot, flying Lancaster bombers during the Second World War, leaving the RAF in 1946, when he took up accountancy. He was appointed a director of the family business Cussen & Co., a wholesale and retail tobacconists with outlets in London and South Wales. When Ruth was sacked as manager of the Carroll Club, she moved in with Cussen at 20 Goodward Court, Devonshire Street, north of Oxford Street, becoming his mistress.

The relationship with Blakely continued, however, and became increasingly violent and embittered as Ellis and Blakely continued to see other people. Blakely offered to marry Ellis, to which she consented, but she lost another child in January 1955, after a miscarriage induced by a punch to the stomach in an argument with Blakely.

On Easter Sunday, 10 April 1955, Ellis took a taxi from Cussen's home to a second floor flat at 29 Tanza Road, Hampstead, the home of Anthony and Carole Findlater and where she suspected Blakely might be. As she arrived, Blakely’s car drove off, so she paid off the taxi and walked the quarter mile to the

Magdala, a four-storey public house in South Hill Park, Hampstead, where she found Blakely’s car parked outside.

At around 9:30 pm David Blakely and his friend Clive Gunnell emerged. Blakely passed Ellis waiting on the pavement when she stepped out of Henshaws Doorway, a newsagent next to the Magdala. He ignored her when she said "Hello, David," then shouted "David!"

As Blakely searched for the keys to his car, Ellis took a .38 calibre Smith & Wesson Victory model revolver from her handbag and fired five shots at Blakely. The first shot missed and he started to run, pursued by Ellis round the car, where she fired a second, which caused him to collapse onto the pavement. She then stood over him and fired three more bullets into him. One bullet was fired less than half an inch from Blakely's back and left powder burns on his skin.

Ellis was seen to stand mesmerised over the body and witnesses reported hearing several distinct clicks as she tried to fire the revolver's sixth and final shot, before finally firing into the ground. This bullet ricocheted off the road and injured Gladys Kensington Yule, 53, the wife of a local banker, in the base of her thumb, as she walked to the Magdala.

Ellis, in a state of shock, asked Gunnell, "Will you call the police, Clive?" She was arrested immediately by an off-duty policeman, Alan Thompson (PC 389), who took the still-smoking gun from her, put it in his coat pocket, and heard her say, "I am guilty, I'm a little confused." She was taken to Hampstead police station where she appeared to be calm and not obviously under the influence of drink or drugs. She made a detailed confession to the police and was charged with murder. Blakely's body was taken to hospital with multiple bullet wounds to the intestines, liver, lung, aorta and windpipe.

LACK OF INVESTIGATION & REPRESENTATION

No solicitor was present during Ellis's interrogation or during the taking of her statement at Hampstead police station, although three police officers were present that night at 11:30 pm: Detective Inspector Gill, Detective Inspector Crawford and Detective Chief Inspector Davies. Ellis was still without legal representation when she made her first appearance at the magistrates' court on 11 April 1955 and held on remand.

She was twice examined by principal Medical Officer, M. R. Penry Williams, who failed to find evidence of mental illness and she undertook an electroencephalography examination on 3 May that failed to find any abnormality. While on remand in Holloway, she was examined by psychiatrist Dr D. Whittaker for the defence, and by Dr A. Dalzell on behalf of the Home Office. Neither found evidence of insanity.

TRIAL AND EXECUTION

On 20 June 1955, Ellis appeared in the Number One Court at the Old Bailey, London, before Mr Justice Havers. She was dressed in a black suit and white silk blouse with freshly bleached and coiffured blonde hair. Her lawyers expressed concern about her appearance (and dyed blonde hair), but she did not alter it to appear less striking.

"It's obvious when I shot him I intended to kill him."

— Ruth Ellis, in the witness box at the Old Bailey, 20 June 1955.

This was her answer to the only question put to her by Christmas Humphreys, counsel for the Prosecution, who asked, "When you fired the revolver at close range into the body of David Blakely, what did you intend to do?"[9] The defending counsel, Aubrey Melford Stevenson supported by Sebag Shaw and Peter Rawlinson, would have advised Ellis of this possible question before the trial began, because it is standard legal practice to do so. Her reply to Humphreys's question in open court guaranteed a guilty verdict and therefore the mandatory death sentence which followed. The jury took 14 minutes to convict

her. She received the sentence, and was taken to the condemned cell at Holloway.

In a 2010 television interview Mr Justice Havers’s grandson, actor Nigel Havers, said his grandfather had written to the Home Secretary Gwilym Lloyd George recommending a reprieve as he regarded it as a crime passionnel, but received a curt refusal, which was still held by the family. It has been suggested that the final nail in her coffin was that an innocent passer-by had been injured.

Reluctantly, at midday on 12 July 1955, the day before her execution, Ellis, having dismissed Bickford, the solicitor chosen for her by her friend Desmond Cussen, made a statement to the solicitor Victor Mishcon (whose law firm had previously represented her in her divorce proceedings but not in the murder trial) and his clerk, Leon Simmons. She revealed more evidence about the shooting and said that the gun had been provided by Cussen, and that he had driven her to the murder scene. Following their 90-minute interview in the condemned cell, Mishcon and Simmons went to the Home Office, where they spoke to a senior civil servant about Ellis's revelations. The authorities made no effort to follow this up and there was no reprieve.

In a final letter to David Blakely's parents from her prison cell, she wrote "I have always loved your son, and I shall die still loving him."

Ever since Edith Thompson's execution in 1923, condemned female prisoners had been required to wear thick padded calico knickers, so just prior to the allotted time, Warder Evelyn Galilee, who had guarded Ellis for the previous three weeks, took her to the lavatory. Warder Galilee said, “I’m sorry, Ruth, but I’ve got to do this.” They had tapes back and front to pull. Ellis said “Is that all right?” and “Would you pull these tapes, Evelyn? I’ll pull the others.” On re-entering the condemned cell, she took off her glasses, placed them on the table and said "I won't be needing these anymore."

Thirty seconds before 9 am on Wednesday 13 July, the official hangman, Albert Pierrepoint, and his assistant, Royston Rickard, entered the condemned cell and escorted Ruth 15 feet (4.6 m) to the execution room next door. She had been weighed at 103 pounds (47 kg) the previous day and a drop of 8 ft 4in was set. Pierrepoint carried out the execution in just 12 seconds and her body was left hanging for an hour. Her autopsy report, by the pathologist Dr Keith Simpson, was made public.

The Bishop of Stepney, Joost de Blank, visited Ellis just before her death, and she told him, "It is quite clear to me that I was not the person who shot him. When I saw myself with the revolver I knew I was another person." These comments were made in a London evening paper of the time, The Star.

PUBLIC REACTION

The case caused widespread controversy at the time, evoking exceptionally intense press and public interest to the point that it was discussed by the Cabinet.

On the day of her execution the Daily Mirror columnist Cassandra wrote a column attacking the sentence, writing "The one thing that brings stature and dignity to mankind and raises us above the beasts will have been denied her – pity and the hope of ultimate redemption." A petition to the Home Office asking for clemency was signed by 50,000 people, but the Conservative Home Secretary Major Gwilym Lloyd George rejected it.

The novelist Raymond Chandler, then living in Britain, wrote a scathing letter to the Evening Standard, referring to what he described as "the medieval savagery of the law".

Though the British public as a whole supported the execution of a murderess, the hanging helped strengthen public support for the abolition of the death penalty, which was halted in practice for murder in Britain 10 years later (the last execution in the UK occurred in 1964). Reprieve was by then commonplace. According to one statistical account, between 1926 and 1954, 677 men and 60 women had been sentenced to death in England and Wales, but only 375 men and seven women had been executed.

In the early 1970s, John Bickford, Ellis's solicitor, made a statement to Scotland Yard from his home in Malta. He recalled that Desmond Cussen told him in 1955 that Ellis lied at the trial. Bickford had kept the information to himself. After Bickford's confession a police investigation followed but no further action regarding Cussen was taken.

Anthony Eden, the Prime Minister at the time, made no reference to the Ruth Ellis case in his memoirs, nor is there anything in his papers. He accepted that the decision was the responsibility of the Home Secretary, but there are indications that he was troubled by it.

Foreign newspapers observed that the concept of the 'crime passionnel' seemed alien to the British.

CRIMES

OF PASSION

Women

in particular are prone to all manner of crimes relating to passion

- and passion can take many forms. Murder was a popular finale, but the

most prevalent is fabricating a sexual allegation after a man upsets a

woman or girl. The sexual allegation is favorite because it carries

virtually no come back if it goes wrong and it totally destroys the life

of the male victim. In many case death would have been preferable. Once a

sexual allegation has been made, a conviction under the present system

where you are guilty until proven innocent, is virtually guaranteed and

today in Britain all it takes is the unsupported testimony of a vengeful

filly. Before the media hysteria relating to such allegations, a judge was

obliged to point out to a jury that it was dangerous to convict on just

the say so of a woman [scorned].

FAMILY AFTERMATH

In 1969 Ellis’s mother, Berta Neilson, was found unconscious in a gas-filled room in her flat in Hemel Hempstead. She never fully recovered and did not speak coherently again. Ellis's husband, George Ellis, descended into alcoholism and hanged himself in 1958. Her son, Andy, who was 10 at the time of his mother's hanging, committed suicide in a bedsit in 1982, shortly after desecrating his mother's grave. The trial judge, Sir Cecil Havers, had sent money every year for Andy's upkeep, and Christmas Humphreys, the prosecution counsel at Ellis's trial, paid for his funeral. Ellis's daughter, Georgina, who was three when her mother was executed, was adopted when her father hanged himself three years later. She died of cancer aged 50.

CAMPAIGN FOR PARDON

The case continues to have a strong grip on the British imagination and in 2003 was referred back to the Court of Appeal by the

Criminal Cases Review

Commission. The Court firmly rejected the appeal, although it made clear that it could rule only on the conviction based on the law as it stood in 1955, and not on whether she should have been executed.

The court was critical of the fact that it had been obliged to consider the appeal:

We would wish to make one further observation. We have to question whether this exercise of considering an appeal so long after the event when Mrs Ellis herself had consciously and deliberately chosen not to appeal at the time is a sensible use of the limited resources of the Court of Appeal. On any view, Mrs Ellis had committed a serious criminal offence. This case is, therefore, quite different from a case like

'Hanratty [2002] 2 Cr App R 30' where the issue was whether a wholly innocent person had been convicted of murder. A wrong on that scale, if it had occurred, might even today be a matter for general public concern, but in this case there was no question that Mrs Ellis was other than the killer and the only issue was the precise crime of which she was guilty. If we had not been obliged to consider her case we would perhaps in the time available have dealt with 8 to 12 other cases, the majority of which would have involved people who were said to be wrongly in custody.

In July 2007 a petition was published on the 10 Downing Street website asking Prime Minister

Gordon Brown to reconsider the Ruth Ellis case and grant her a pardon in the light of new evidence that the Old Bailey jury in 1955 was not asked to consider. It expired on 4 July 2008.

BURIAL

Ellis was buried in an unmarked grave within the walls of Holloway Prison, as was customary for executed prisoners. In the early 1970s the prison underwent an extensive programme of rebuilding, during which the bodies of all the executed women were exhumed for reburial elsewhere. Ellis's body was reburied in the churchyard extension of St Mary's Church in Amersham, Buckinghamshire. The headstone in the churchyard was inscribed "Ruth Hornby 1926–1955". Her son, Andy, destroyed the headstone shortly before he committed suicide in 1982.

The remains of the four other women executed at Holloway, Styllou Christofi, Edith Thompson, Amelia Sach and Annie Walters, were reburied in a single grave at Brookwood Cemetery.

Coincidentally, Styllou Christofi, who was executed in December 1954, lived at 11 South Hill Park in Hampstead, with her son and daughter-in-law, a few yards from the Magdala public house at number 2a, where David Blakely was shot four months later.

FILM & TELEVISION

In 1980, the third episode of the first series of the ITV drama series Lady Killers recreated the court case, with Ellis played by Georgina Hale.

The first cinema portrayal of Ellis came with the release of the 1985 movie Dance with a Stranger, directed by Mike Newell and featuring Miranda Richardson as Ellis.

Both Ellis's story and the story of Albert Pierrepoint are retold in the stage play Follow Me, written by Ross Gurney-Randall and Dave Mounfield and directed by Guy Masterson. It premièred at the Assembly Rooms as part of the 2007 Edinburgh Festival Fringe.

In the film Pierrepoint (2006), Ellis was portrayed by Mary Stockley.

Diana Dors, who had starred in Lady Godiva Rides Again, in which Ellis had had a minor, uncredited role, played a character resembling (though not based on) Ellis in the 1956 British film Yield to the Night, directed by J. Lee Thompson.

The case was the basis for Amanda Whittington's play The Thrill of Love. It premiered at the New Vic Theatre, Newcastle-under-Lyme, in February 2013 and subsequently played at St James Theatre London with Faye Castelow in the main role.

A FINE DAY FOR A HANGING

Ruth Ellis was the last woman to be hanged in Britain — an execution that appalled the world. On Saturday we told how she was beaten and abused by the men in her life before finally snapping and shooting dead her faithless, violent lover David Blakely. Today, in our final gripping extract from a forensically researched new book, we reveal how vital evidence that would have saved her from the gallows was ignored. . .

Two hours after the shooting, while David Blakely’s body was lying in the mortuary, Ruth Ellis was questioned by three detectives in Hampstead police station. It was 11.30pm. One of the detectives recalled: ‘She had a cigarette and she was completely calm

...... she really couldn’t care less what was going to happen to her.’

She was cautioned: ‘You are not obliged to say anything at all about this unless you wish to do so, but whatever you say will be taken down in writing and may be given in evidence.’

‘I am guilty,’ Ruth said decisively. Then she hesitated: ‘I am rather confused.’

She began answering the questions, which then became her statement. She was asked where she got the gun. She explained that it had been given to her as security for money about three years ago in a club by a man whose name she did not remember.

Then she uttered the crucial words: ‘When I put the gun in my bag, I intended to find David and shoot him.’

The police were puzzled. Ruth seemed fragile, only 5ft 2in and less than 7st, and calm and quiet rather than driven by raging emotions. Moreover, her story about the gun did not add up: it was too well-oiled to have been left in a drawer for three years.

The following day Ruth was told she would be driven to nearby Hampstead magistrates’ court to be formally charged with Blakely’s murder.

She nodded, and then remarked: ‘An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. I will hang.’

That same day Desmond Cussen gave a statement to police. He described the past two years, his relationship with Ruth and admitted to competing for Ruth with Blakely.

He also discussed his part as her unofficial chauffeur and the beatings Ruth had received from Blakely.

But while he admitted to having spent Easter Sunday with Ruth and her ten-year-old son Andre, he claimed to have dropped her off at her rented room at 7.30pm and said he hadn’t seen her since.

What he did not say was that he had not only given Ruth the gun, but had also taught her how to use it — and had driven her to the Hampstead street where she later killed Blakely.

Though he did eventually confess all this to Ruth’s solicitor, John Bickford, it was never brought up at her trial — because Bickford thought it would affect the chances of achieving a verdict of manslaughter rather than murder.

It was Bickford’s job to defend Ruth, but she did not make it easy. She was determined to shield Cussen and was vehement that she did not want her life to be spared.

She firmly rejected his request that she plead insanity. ‘I took David’s life and I don’t ask you to save mine,’ she told him. ‘I don’t want to live.’

As she waited in Holloway for her trial, warders noted she was extremely quiet and co-operative. With visitors she made bright small talk — ‘almost as though we were at a tea party,’ noted one in bewilderment — and spent her days reading.

She put on several pounds, probably because she was eating a proper diet for the first time in her life, and wrote polite letters thanking friends and well-wishers.

She cried only once — when she asked for, and was given, photographs of Blakely’s corpse.

Today it seems clear that, driven to the edge of madness by her ill-treatment at the hands of Blakely, she was suffering from post-traumatic stress.

But in 1955 the term did not exist. Nor did the defence of diminished responsibility, which would almost certainly have saved her from the gallows.

She had been abused all her life. She had just lost her baby after being viciously beaten by the man she loved, and was desperately unwell.

Because of her relationship with him she had lost her job, and with it her flat. She had given him most of the money she’d earned.

She was also feeling humiliated because, having asked her to marry him, he had then abandoned her for a weekend of partying with the Findlaters, middle-class friends in Hampstead who despised her and thought she was common.

She had been given refuge by Desmond Cussen, who wanted Blakely out of the way so he could have Ruth to himself.

He had given her a gun, taught her how to use it and had then driven her, three nights in a row, to the street in Hampstead where Blakely was staying with the Findlaters.

It was only to expose the part the Findlaters had played in Blakely’s ill-treatment of Ruth that weekend that she agreed to plead not guilty. She thought they were malicious snobs who she felt were to blame for his refusing to see her, driving her to breaking point. She even wrote to Blakely’s mother to explain this, and to apologise for killing her son:

‘The two people I blame for David’s death, and my own, are the Findlayters (sic). No dought (sic) you will not understand this, but perhaps before I hang you will know what I mean. Please excuse my writing, but the pen is shocking.

‘I implore you to try to forgive David for living with me, but we were very much in love with one and other (sic). Unfortunately, David was not satisfied with one woman in his life. I have forgiven David, I only wish I could have found it in my heart to have forgiven when he was alive.

‘Once again, I say I am very sorry to have caused you this misery and heartache. I shall die loving your son. And you should feel content that his death has been repaid.

‘Goodbye. Ruth Ellis.’

As the trial loomed, Ruth’s outward calm masked her inner turmoil. Notes by the prison doctor record that she was ‘very upset about her children’s future

... regrets that she won’t be able to see them grow up’. She could not sleep, despite sedatives.

Her blonde hair had faded in prison and Ruth was desperate to dye it so she would not appear in court with dark roots.

Her defence team were uncomfortable, sensing that her bleached hair would only encourage the jury to view her with disdain. But Ruth insisted. The trial began on Monday, June 20, 1955, at the Old Bailey to enormous Press and public interest.

As Ruth was led up from the cells, a shout came from the public gallery: ‘Blonde tart.’ The charge was read out and she pleaded ‘not guilty’ in a clear, high voice.

Ruth had spent her life being let down by men — and her trial was to prove no exception.

From the moment of her arrest, she was questioned only by men: policemen, solicitors and barristers. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that they all allowed themselves to be swayed by class prejudice — the fact she was a former nightclub hostess while the man she’d murdered was from a well-respected and wealthy family.

Her anger and despair were often referred to as ‘hysterical’, when the often unhinged behaviour of the two most prominent men in her life — David Blakely and her former husband George Ellis — was never described in such terms.

Ruth’s leading defence barrister, Melford Stevenson QC, had almost no criminal law experience and little sympathy towards women.

The prosecution outlined their case. Stevenson gave the prosecution witnesses only the most cursory cross examinations and his questioning of Ant Findlater was brief and feeble.

As far as Ruth was concerned, he had utterly failed to expose the part the Findlaters had played in events. From that point she seemed deflated and defeated.

The judge, Mr Justice Havers, later said her defence was ‘so weak

... it was non-existent’.

He also said he had not been convinced by Ruth’s story of how she came to have a gun in the first place and suspected someone had given it to her. But he added: ‘The defence counsel never mentioned it, and I can only act on the evidence put before me.’

Ruth’s fate in court also had much to do with the fact she did not conform to the stereotype of a wronged woman who had killed her lover through jealousy.

She appeared in court with platinum hair, was calm under questioning, frank about her sexual relationship with Blakely and Cussen, did not present herself as a victim and appeared unemotional.

As for the extreme abuse she had suffered all her life — from the beatings and attempted rape she had endured at the hands of her father when she was a child, to her husband’s use of her as a punchbag and the frequent beatings meted out to her by Blakely, the last of which, only two weeks earlier, had caused her to miscarry — much of it was not mentioned.

The fact that Blakely regularly beat her was considered largely irrelevant by the barristers and solicitors whose job it was to defend her.

Indeed, the judge made a point of telling the jury to ignore the fact she had been abused by him. Ruth, he said, was: ‘A young woman, you may think, badly treated by the deceased man. Nothing of that sort must enter into your consideration

... according to our law it is no defence ... to prove that she was a jealous woman and had been badly treated by her lover and was in ill-health.’ The trial lasted less than two days.

After just half an hour of consideration, the jury returned their unanimous verdict: Guilty. There was no plea for mercy.

Mr Justice Havers slowly picked up the small black square of silk and placed it on his head. Then he turned to address her: ‘Ruth Ellis, the jury have convicted you of murder

... You will suffer death by hanging.’ Ruth bowed her head and said quietly: ‘Thanks.’

The execution date was set for 9am Wednesday July 13. American crime writer Raymond Chandler, who was staying in London at the time, was so outraged he wrote a letter to the Evening Standard.

‘This thing haunts and, so far as I may say it, disgusts me as something obscene,’ he wrote. ‘I am not referring to the trial, of course, but to the medieval savagery of the law

... I have been tormented for a week at the idea that a highly civilised people should put a rope round the neck of Ruth Ellis and drop her through a trap and break her neck. This was a crime of passion under considerable provocation. No other country in the world would hang this woman.’

Meanwhile, Ruth waited quietly for her execution. Her sole complaint was that she could not sleep: the naked bulb overhead had to remain lit day and night.

The two prison wardresses assigned to her had fashioned a cardboard lampshade to dim the glare — a small gesture, against prison rules, but the Governor said nothing about it. Each day, they witnessed Ruth submerging her fears about the execution by reading, writing letters, doing jigsaws and making dolls from material brought in by her mother.

On July 12, Ruth was visited by her former solicitor Victor Mishcon. He’d been asked to do so by John Bickford, who was still trying desperately to save Ruth and who wanted Mishcon to ask her how she’d got the gun.

Mishcon asked Ruth if she wanted her son to grow up knowing the truth of what had happened. This seems to have finally persuaded her to tell the true story.

Cussen had not only given her the gun, she said, but had also taught her how to fire it and had driven her across London to find Blakely.

Mishcon immediately told the Home Office. He was sure it offered hope for Ruth, and hoped at the very least for a stay of execution while the police tracked down Cussen to corroborate the statement.

A desperate hunt around London ensued, but Cussen could not be found. The Home Secretary refused to delay the execution, privately noting: ‘If she isn’t hanged tomorrow, she never will be.’

Meanwhile, Ruth had received her last visit from her parents and brother. They spent much of the 30 minutes in silence, not knowing what to say. Ruth, who knew her daughter Georgina by ex-husband George Ellis was being well looked after by a wealthy childless couple, was worried about her son Andre, conceived during an affair with a married Canadian serviceman.

She asked them to look after him and added: ‘When he grows up, see that he understands about me and try to show him that, whatever I did, I loved him all the time.’

Shortly after 2am on July 13, the Home Office rang Mishcon: the new evidence changed nothing. Ruth would be executed in seven hours.

The hangman, Albert Pierrepoint, recalled that Ruth met her death courageously. ‘I have seen some brave men die, but nobody braver than her,’ he said.

The world’s Press reacted to Ruth’s execution with disgust. It was seen as bringing shame on Britain. The campaign to abolish capital punishment drew 33,000 members in its first few months.

Just two years later, in March 1957, the Homicide Act was introduced allowing the defence of diminished responsibility.

More than half of the 65 people condemned to death after the introduction of the Homicide Act were reprieved.

Ten years after Ruth’s execution, on November 8, 1965, the Murder (Abolition Of The Death Penalty) Act was passed, suspending capital punishment, and in December 1969 it was permanently abolished.

Almost everyone connected with Ruth’s case was profoundly affected by it for the rest of their lives.

Her daughter Georgina grew up to attain notoriety, dying her hair blonde like her mother and having high-profile affairs. She died of cancer aged 50. Andre was looked after by her parents, but became a schizophrenic and drug addict, and committed suicide in 1982.

His funeral was paid for by Christmas Humphreys, the prosecuting lawyer at Ruth’s trial — and it has always been said Mr Justice Havers had sent Andre money every year at Christmas.

Ruth’s former husband George Ellis committed suicide in 1958. Desmond Cussen died a lonely alcoholic, as did her solicitor John Bickford, who remained haunted by the case for the rest of his life.

Years later, asked in a TV documentary whether he could have done more to help Ruth, he replied: ‘If I’d been a stronger man or a more determined fellow, or didn’t mind making a spectacle of myself, perhaps.’ His eyes welled with tears. ‘Sorry.’

A FINE DAY FOR A HANGING

Adapted from A Fine Day For A Hanging by Carol Ann Lee, to be published by Mainstream

at £11.99. © 2012 Carol Ann Lee. To order a copy for £10.99 (incl p&p), tel: 0843 382 0000.

YOUTUBE

|

|

|

|

|

|

Works

of fiction about prisons, some of which are based on real events |

|

|

|

|

|

LINKS

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruth_Ellis

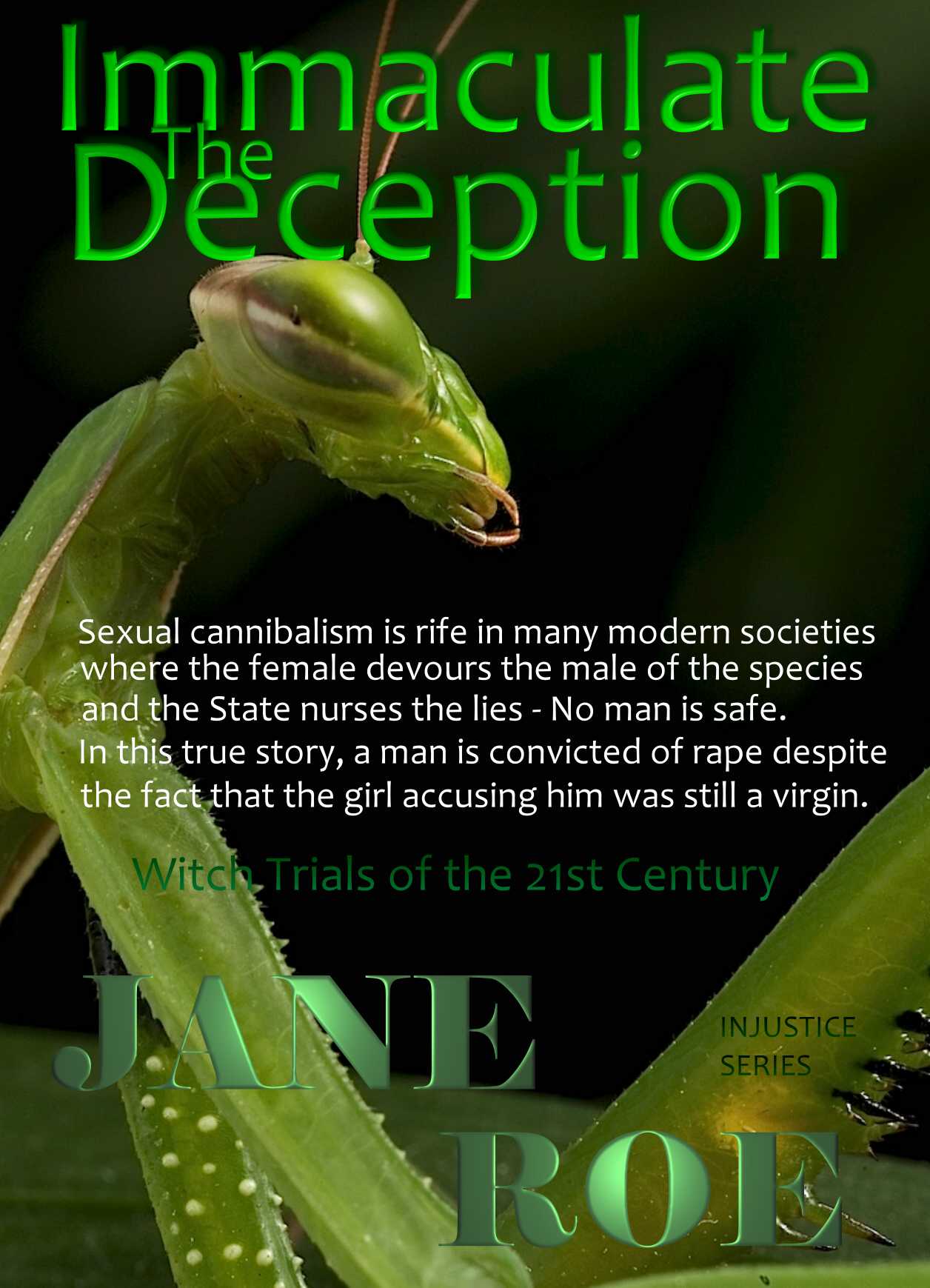

Sexual

cannibalism in humans is commonplace where the (UK) state still pays

bunny-boilers to fabricate allegations - despite the untenable ratio of

false allegations. This is called Noble

Cause Corruption, so named because the cause (more convictions of

rapists and perverts) is noble, but the means (convicting significant

numbers of innocent men) is corrupt. A decent justice system is one where

convictions are safe; where an appeal is guaranteed and where the court

system does not refuse appellants the evidence for their barristers to

perfect grounds of appeal. Unlike most European countries, the right of

appeal in the UK in not mandatory and the discretionary single judge paper

system is open to startling abuses. This book is based on a real case

study, that reveals the fatal flaws in the English justice system. No man

in England is safe until these issues are dealt with - it could happen to

anyone.

|