The Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007 is a landmark in law. For the first time, companies and organisations can be found guilty of corporate manslaughter as a result of serious management failures resulting in a gross breach of a duty of care.

The common law test to impose criminal responsibility on a company only arises where a person's gross negligence has led to another person's death and (under the "identification doctrine") that person is a "controlling mind", whose actions and intentions can be imputed to the company (that is, a person in control of the company's affairs to a sufficient degree that the company can fairly be said to think and act through him). This is tested by reference to the detailed work patterns of the manager, and the job title or description given to that person is irrelevant, but there is often no single person who acts as a "controlling mind", particularly in large companies, and many issues of health and safety are delegated to junior managers who are not "controlling minds".

On 6 March 1987, 193 people died when the Herald of Free Enterprise capsized. Although individual employees failed in their duties, the Sheen Report severely criticised the attitude to safety prevalent in P&O, stating:

All concerned in management ... were at fault in that all must be regarded as sharing responsibility for the failure of management. From top to bottom the body corporate was infected with the disease of sloppiness.

There was significant institutional resistance to the appropriateness of using the criminal law in general, and homicide charges in particular in this type of situation. Judicial review of the coroner's inquest persuaded the Director of Public Prosecutions to bring manslaughter charges against P&O European Ferries and seven employees, but the trial judge ruled that there was no evidence that one sufficiently senior member of the company's management could be said to have been negligent.

A subsequent appeal confirmed that corporate manslaughter is a charge known to English criminal law, and with the revival of gross negligence as a mens rea for manslaughter, it was thought that prosecutions might succeed. However, a prosecution of Great Western Trains following the Southall rail crash collapsed because "the Crown was not in a position to satisfy the doctrine of identification" (Turner J). Only the company itself and the train driver, Mr Larry Harrison, were prosecuted. Since the train driver is not someone of a managerial or directorial level, the case against him was dismissed in the opening arguments. Because the only other defendant was GWT, a corporation, this meant that it was impossible to identify a controlling mind for the purposes of holding an individual personally liable for manslaughter.

In English law, proving corporate manslaughter and securing a conviction of an individual where the corporation involved is a small concern are easier where it is easier to identify a "controlling mind" (in R v OLL Ltd, 1994, about the Lyme Bay canoeing tragedy, managing director Peter Kite was convicted), but efforts to convict people in larger corporate entities tends to fail as the management structure is more diffuse making this identification more difficult. Instead, the prosecution stands more chance of pursuing a case successfully if it prosecutes simply on the grounds of a safety breach under the

Health and Safety at Work Act 1974.

Following R v. Prentice, a breach of duty amounts to 'gross negligence' when there is:

indifference to an obvious risk of injury to health; actual foresight of the risk coupled with the determination nevertheless to run it; appreciation of the risk coupled with an intention to avoid it but also coupled with such a high degree of negligence in the attempted avoidance as the jury consider justifies conviction, and inattention or failure to advert to a serious risk which goes "beyond inadvertence" in respect of an obvious and important matter which the defendant's duty demanded he should address.

The Law Commission's 1996 report on involuntary manslaughter found that the gross negligence formula overcomes the problems of having to find one particular officer who has the mens rea for the offence and allows emphasis to be placed on the company’s attitude to safety. This question would only arise where the company has chosen to enter a field of activity that carries a risk to others, such as transport, manufacture or medical care. The steps the company has taken to discharge the "duty of safety" and the systems devised for running its business, will be directly relevant. Although only expressed as a provisional view, it is significant that the Law Commission echoes here the recognition of corporate safety systems voiced in the Seaboard case. Thus, a real tension is exposed between the paradigm of criminal culpability based on individual responsibility and the increasing recognition of the potential for harm inherent in large scale corporate activity.

The government issued a consultation paper in 2000, proposing reforms to the law to implement the recommendations of the Law Commission. A draft Corporate Manslaughter Bill was published in March 2005, and the Queen's Speech on 17 May 2005 included a reference to an Act of Parliament to be passed in 2005/6 to widen the scope for prosecutions for corporate manslaughter.

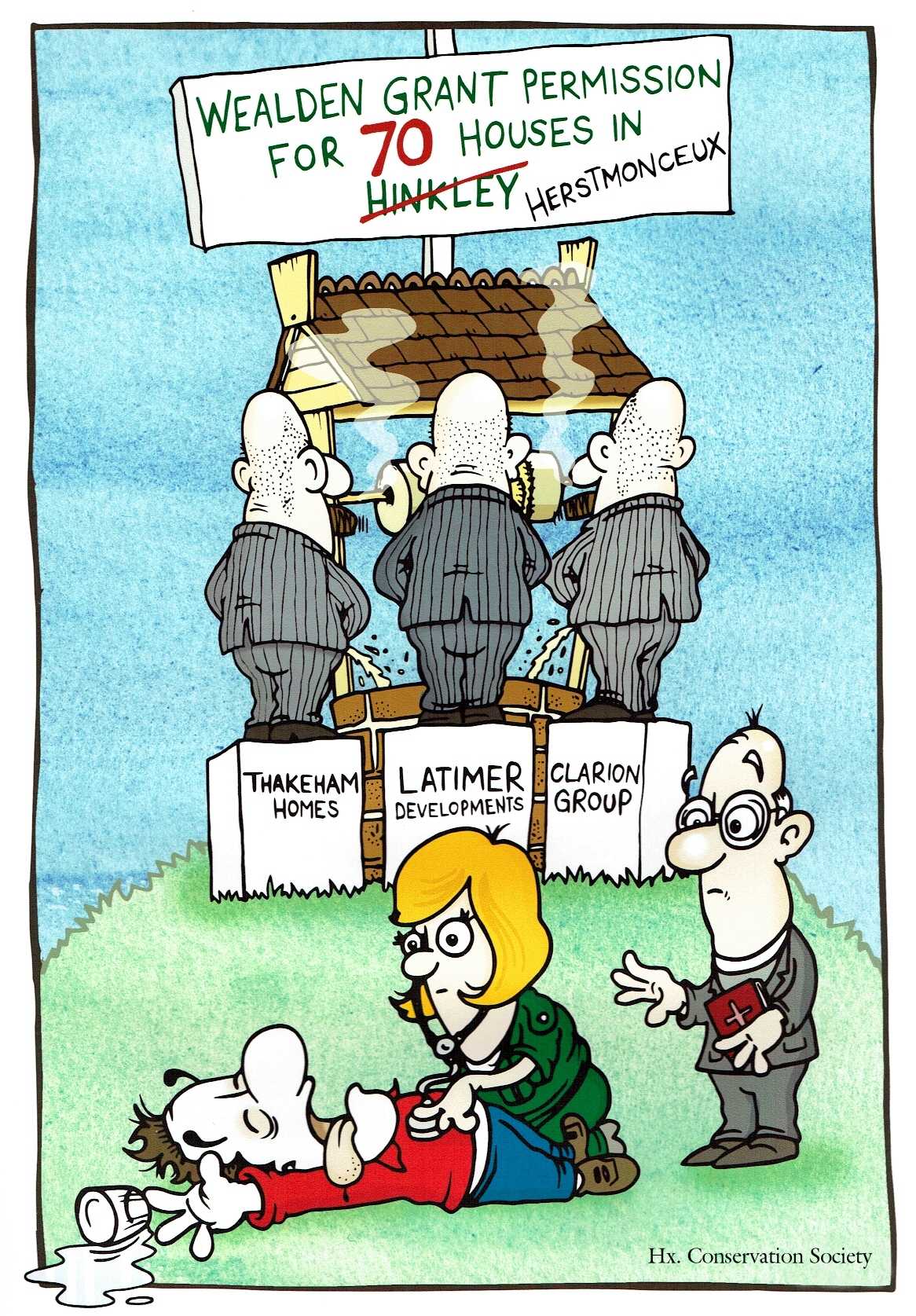

WATER

CONTAMINATION - If houses are built on the hill that supplies the last

surviving well in Herstmonceux, all of those who presently enjoy a

sustainable water supply are likely to be poisoned by pesticides from a

number of the

gardens of the proposed housing - at the moment that looks like being 28

units positioned directly above and in the groundwater soakage line of fire. In addition, where the hard standings of

the proposed 70 houses are to be gully drained to a point lower than the

twin wells, rainwater soakage that supplies the wells will be diverted away

potentially starving the wells of water, save that from the garden areas

that are impossible to gully.

The amusing cartoon above portrays the situation that perhaps the present developers

(Clarion,

Latimer,

Thakeham)

were not aware of, when they bought into a situation that they

should have been able to rely on.

Unfortunately, the council concerned and

the advisers to the original applicants (Gleeson

Developments) appear to have been less diligent

than they might have been in the rush to profit from a windfall situation.

The question that is probably on your lips is: "Was that an

oversight, or was it deliberate"?

Another

problem that is rearing it's head with many developments is that

corporations are building what they want to build without constructing the

affordable unit quotient or making improvement to drainage and access

roads that some council's have been kind enough to overlook at the grant

stage with a promise from developers to overcome, when in fact those

developers simply vanish without trace, leaving nobody to pick up the tab.

In other words development is never completed to a stage where flooding

and other contamination measures are safe.

CORPORATE

MANSLAUGHTER and HOMICIDE ACT 2007

Section

1 The offence

(1) An organisation to which this section applies is guilty of an offence if the way in which its activities are managed or

organised —

(a) causes a person's death, and

(b) amounts to a gross breach of a relevant duty of care owed by the organisation to the deceased.

(2) The organisations to which this section applies are —

(a) a corporation;

(b) a department or other body listed in Schedule 1;

(c) a police force;

(d) a partnership, or a trade union or employers' association, that is an employer.

(3) An organisation is guilty of an offence under this section only if the way in which its activities are managed or organised by its senior management is a substantial element in the breach referred to in subsection (1).

(4) For the purposes of this Act—

(a) “relevant duty of care” has the meaning given by section 2, read with sections 3 to 7;

(b)a breach of a duty of care by an organisation is a “gross” breach if the conduct alleged to amount to a breach of that duty falls far below what can reasonably be expected of the organisation in the circumstances;

(c) “senior management”, in relation to an organisation, means the persons who play significant roles in—

(i) the making of decisions about how the whole or a substantial part of its activities are to be managed or organised, or

(ii) the actual managing or organising of the whole or a substantial part of those activities.

(5) The offence under this section is called —

(a) corporate manslaughter, in so far as it is an offence under the law of England and Wales or Northern Ireland;

(b) corporate homicide, in so far as it is an offence under the law of Scotland.

(6) An organisation that is guilty of corporate manslaughter or corporate homicide is liable on conviction on indictment to a fine.

(7) The offence of corporate homicide is indictable only in the High Court of Justiciary.

S. 2 Meaning of “relevant duty of care”

(1) A “relevant duty of care”, in relation to an organisation, means any of the following duties owed by it under the law of

negligence —

(a) a duty owed to its employees or to other persons working for the organisation or performing services for it;

(b) a duty owed as occupier of premises;

(c) a duty owed in connection with —

(i) the supply by the organisation of goods or services (whether for consideration or not),

(ii) the carrying on by the organisation of any construction or maintenance operations,

(iii) the carrying on by the organisation of any other activity on a commercial basis, or

(iv) the use or keeping by the organisation of any plant, vehicle or other thing;

(d) a duty owed to a person who, by reason of being a person within subsection (2), is someone for whose safety the organisation is responsible.

(2)A person is within this subsection if —

(a) he is detained at a custodial institution or in a custody area at a

court[ a police station or customs premises];

[F2 (aa)he is detained in service custody premises;]

(b) he is detained at a removal centre[a short-term holding facility or in pre-departure accommodation];

(c) he is being transported in a vehicle, or being held in any premises, in pursuance of prison escort arrangements or immigration escort arrangements;

(d) he is living in secure accommodation in which he has been placed;

(e) he is a detained patient.

(3) Subsection (1) is subject to sections 3 to 7.

(4) A reference in subsection (1) to a duty owed under the law of negligence includes a reference to a duty that would be owed under the law of negligence but for any statutory provision under which liability is imposed in place of liability under that law.

(5) For the purposes of this Act, whether a particular organisation owes a duty of care to a particular individual is a question of law.

The judge must make any findings of fact necessary to decide that question.

(6) For the purposes of this Act there is to be disregarded —

(a) any rule of the common law that has the effect of preventing a duty of care from being owed by one person to another by reason of the fact that they are jointly engaged in unlawful conduct;

(b) any such rule that has the effect of preventing a duty of care from being owed to a person by reason of his acceptance of a risk of harm.

(7) In this section —

“construction or maintenance operations” means operations of any of the following

descriptions —

(a) construction, installation, alteration, extension, improvement, repair, maintenance, decoration, cleaning, demolition or dismantling

of —

(i) any building or structure,

(ii) anything else that forms, or is to form, part of the land, or

(iii) any plant, vehicle or other thing;

(b) operations that form an integral part of, or are preparatory to, or are for rendering complete, any operations within paragraph (a)

S. 9 Power to order breach etc to be remedied

(1) A court before which an organisation is convicted of corporate manslaughter or corporate homicide may make an order (a “remedial order”) requiring the organisation to take specified steps to

remedy —

(a) the breach mentioned in section 1(1) (“the relevant breach”);

(b)any matter that appears to the court to have resulted from the relevant breach and to have been a cause of the death;

(c)any deficiency, as regards health and safety matters, in the organisation's policies, systems or practices of which the relevant breach appears to the court to be an indication.

(2) A remedial order may be made only on an application by the prosecution specifying the terms of the proposed order.

Any such order must be on such terms (whether those proposed or others) as the court considers appropriate having regard to any representations made, and any evidence adduced, in relation to that matter by the prosecution or on behalf of the organisation.

(3) Before making an application for a remedial order the prosecution must consult such enforcement authority or authorities as it considers appropriate having regard to the nature of the relevant breach.

(4) A remedial order —

(a) must specify a period within which the steps referred to in subsection (1) are to be taken;

(b) may require the organisation to supply to an enforcement authority consulted under subsection (3), within a specified period, evidence that those steps have been taken.

A period specified under this subsection may be extended or further extended by order of the court on an application made before the end of that period or extended period.

(5) An organisation that fails to comply with a remedial order is guilty of an offence, and liable on conviction on indictment to a fine.

S. 19 Convictions under this Act and under health and safety legislation

(1) Where in the same proceedings there is —

(a) a charge of corporate manslaughter or corporate homicide arising out of a particular set of circumstances, and

(b) a charge against the same defendant of a health and safety offence arising out of some or all of those circumstances,

the jury may, if the interests of justice so require, be invited to return a verdict on each charge.

(2) An organisation that has been convicted of corporate manslaughter or corporate homicide arising out of a particular set of circumstances may, if the interests of justice so require, be charged with a health and safety offence arising out of some or all of those circumstances.

(3) In this section “health and safety offence” means an offence under any health and safety legislation.

SCHEDULE 1 - LIST OF

GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENTS

Attorney General's Office

Cabinet Office

Central Office of Information

Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service

Crown Prosecution Service

[Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy]

Department for Culture, Media and Sport

[Department for Education]

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

Department for International Development

Department for Transport

Department for Work and Pensions

Department of Health [and Social Care]

Export Credits Guarantee Department

Foreign and Commonwealth Office

Forestry Commission

General Register Office for Scotland

Government Actuary's Department

Her Majesty's Land Registry

Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs

Her Majesty's Treasury

Home Office

Ministry of Defence

Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local

Government

[Ministry of Justice (including the Scotland Office and the Wales Office)]

National Archives

National Archives of Scotland

[National Crime Agency]

National Savings and Investments

National School of Government

Northern Ireland Audit Office

Northern Ireland Office

Office for National Statistics

Office of Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Education and Training in Wales

Ordnance Survey

Public Prosecution Service for Northern Ireland

Registers of Scotland Executive Agency

Royal Mint

Scottish Executive

Serious Fraud Office

Treasury Solicitor's Department

UK Trade and Investment

Welsh Assembly Government

NCSC

ROYAL OPENING - Her Majesty The Queen opened the NCSC on the 17th of

February 2017. There are several agencies in the UK that are supposed to

tackle fraud, cyber crime, drugs, sex trafficking and money laundering,

but when you ask any one of them to take a look at corruption in

Wealden-land, they don't appear too anxious to open a case file. It's

more a case of pass the buck .... and keep passing it ... until the

complainant fades away. Sorry to have to report this to you Your

Majesty, but it is the truth the whole truth and nothing but the truth -

so help me God.

...

...

THE

TELEGRAPH

- ....

THE

INDEPENDENT MARCH

2017 ZEEBRUGGE 30 YEARS ON - Thirty years ago this Monday, shortly after setting out to Dover from the Belgian port of Zeebrugge, the ferry Herald of Free Enterprise capsized with the loss of 193 lives – Britain’s worst peacetime maritime disaster since 1919. Godfrey Holmes examines the catastrophic failings both on the day an in the aftermath, and finds numerous lessons still to be learnt

Imagine free enterprise unchecked, self-reverential. Imagine a “spirit of free enterprise” that places capital above both labour and product. Then imagine a “pride of free enterprise” certain of its own merits; too careless to consult history regarding past shipping disasters; too mean to spare a fiver in order to avert catastrophe. And there – on a cold and miserable night exactly 30 years ago this weekend – we have the sinking of the Herald of Free Enterprise.

Three times this ferry’s owners – owners stubbornly upholding the fiction they weren’t really the owners – were warned about open doors; on a first occasion saying nobody had ever worried about them before; on a second occasion saying they weren’t in the business of telling crew how to do their jobs as specified; on a third occasion saying they were busy, go away.

Thus it was that, early on the evening of Friday 6 March 1987, only 23 minutes into a voyage that should have been routine, and steadily gaining speed to 18 knots an hour, 193 lives were needlessly sacrificed to the frigid waters – 3C – of the

English

Channel. And the keeling over of Townsend Thoresen’s state-of-the-art (1980) “roll-on, roll-off” car, lorry, and foot-passenger ferry the Herald of Free Enterprise took just two minutes. And how terrifying those two minutes.

Already 20 minutes late raising anchor, the Herald was carrying 459 passengers or drivers, 80 tired crew members still to complete their second sailing in a 24-hour window, 81 cars, 47 lorries, three buses. Some lorry drivers down below were taking a shower, eating their sandwiches, resting; while several dozen day-trippers – those who’d joyfully taken advantage of a Sun newspaper offer of Belgium for £1 return – congregated in the lounge for drinks and a chat. Other passengers and crew were getting their bearings along some very long corridors leading wherever. A few “lucky” souls were out outdoors for a breather, still glancing back towards Zeebrugge. A haven of safety. If only.

Yet even as 535 innocents tried to come to terms with their own likely demise, four other people on board had that opportunity to reflect how they might have acted differently: Assistant Boatswain Mark Stanley, the man whose duty it was actually to shut the Herald’s two bow doors; Boatswain Terence Ayling, whose job he considered it not to shut those crucial, life-saving, doors; First Chief Officer Leslie Sabel, one of whose tasks it was to check that those doors had actually been shut; and the Captain David Lewry who could neither see the doors nor communicate with anybody who might know anything about those doors or the (also still open too) stern door.

And who was the fifth man, seated in some plush office in Dover, about to knock off for the weekend? He who issued the orders that his ferries were to steam out of port with their doors still open to save on turn-around time? He who would not concede the £5, at most, that would have fixed a simple bell-push on deck G tinkling through to the bridge that the doors had actually been shut prior to departure?

Roll-on, roll-off ferries, or “ro-ros”, are inherently unstable. Most of the ship is above the waterline, not below. Ro-ros are very flat-bottomed: considered in many quarters not to be “real ships” at all – as if still guided by invisible chain. That is why the Herald’s ingress of water was cataclysmic. You only need to carry an ordinary, water-laden 12-inch dinner plate across your bedroom to understand just how volatile – and wet – the outcome. British Rail’s pioneering ferry, MV Princess Victoria, attempting to traverse the wild Irish Sea from Larne to Stranraer on a fateful night during the even more fateful east coast floods of 31 January and 1 February 1953, went down almost immediately as towering waves beat their way on to its car deck. 133 passengers and crew perished that night, with only 44 survivors: none of those eventually rescued was a ship’s officer. Compare.

Stephen Homewood (more of him later) in his seminal book – still only one of two – concerning the night of 6 March 1987, and its aftermath, Zeebrugge: A Hero’s Story, describes what exactly happened to the Herald: “[We] had gone out of harbour with a gaping hole in the bow caused by open doors. She was also loaded and tilted [three-foot extra] at the front [due to extra ballast fed into the hull in order to accommodate the Port of Zeebrugge’s incompatible gangways]. As her speed increased ... the bow door ramp was pushed into the water, scooping up every bow wave, so allowing hundreds and thousands of gallons of sea water to pour in ... This water settled on the port side, causing that first roll. [Briefly] the ship then steadied; but as more water rushed in, the extra weight sent the ship into its final death roll. Floating on its side for a minute, it [soon and providentially] settled on the sandbank that [mercifully] saved the ship from turning completely turtle.”

Too harrowing it is to recount tales of the (fortunate?) Herald survivors. Suffice to say conditions on board, literally overboard too, were hell. Screams of panic. Smashed windows. The sight of fellow passengers – mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, uncles, aunties, nephews, nieces among them – drowning. Fruitless re-entering into totally unlit areas that only a quarter of an hour before were not only lit, but also warm, relaxing, convivial, safe. Forlorn cries for help. Bouncing, clattering, china, glass, chairs, signage. Inaccessible lockers full of life-belts. Some

life-belts so buoyant as to restrict escape. Jagged metal. Forced-down, therefore unusable, exits. Disorientation. Chaos. Confusion. Concussion. Courage. Exposure. Panic.

Water, water, everywhere.

Also too unfair it would be to identify all bravery displayed that night: modest people who – with only a few moments on a freezing March evening to collect their thoughts – acted before far more passengers in distress perished: no longer seen, no longer heard. Suffice it to acknowledge the miraculous, incredibly selfless, and only incidentally recognised and honoured, contributions of Assistant Purser Stephen Homewood; “human bridge” Andrew Parker; unrecovered Master Chef Michael Skippen; Quartermaster Tom Wilson; and crew members Billy Walker and Leigh Cornelius.

Ironically, three of the men attempting to help their charges most were aforementioned Mark Victor Stanley: he who, startled and alarmed, realised his eyes were closed when he should have been operating that critical hydraulic bow-door closing mechanism; Boatswain Terence Ayling, he who, in common with his superior, and carefree, Chief Officer Leslie Sabel, simply assumed, even then too late, that everything had been done that needed to be done. These three, and their correctly censured Captain Lewry, rarely ever spoke to the press – or to fellow survivors – following the Herald’s sinking. But it is beyond dispute that Mark Stanley, a talented footballer and football manager, who never shed the intolerable burden of his guilt – a very specific, solitary, guilt – died in July 2016, prematurely, aged just 58, a broken man.

So many dates need recalling all these years later: first, midnight 6 March 1987: helicopters, ships too, bringing in an initial, necessarily unrepeated, haul of bodies dead or alive; the rest of March 1987: hospitalisation, convalescence, for some survivors; March through to June 1987: funerals; 14 March 1987: a memorial service in the Church of St Mary the

Virgin, Dover; 15 April 1987: a national memorial service in Canterbury Cathedral, led by Archbishop Robert Runcie and televised by the BBC; throughout April 1987: lifting the Herald of Free Enterprise – so facilitating the grim task of recovering the last 77 of a total 193 dead bodies; 26 April 1987: Mr Justice Barry Sheen, Admiralty Judge of the High Court, opening his 29-day public inquiry; October 1987: convening of official coroner’s inquest (jury verdict: unlawful killings); December1987: Order of St John awards, Clerkenwell, London; also P&O’s dedication of a small Kentish wood dedicated to victims of the Herald; March 1988: HM Elizabeth II herself awarding three

Queen’s Gallantry Medals, and two George Medals – one, deservedly, to amazingly brave passenger Andrew Parker; the other, posthumously to Michael Skippen –, as part of her New Year Honours; 6 March 1988: dedication of a specially commissioned stained-glass window in Dover’s parish church; September 1990: abortive criminal trials of seven accused, charged with gross negligence; P&O: charged with corporate

manslaughter; September 1994: the almost carbon-copy sinking of the Estonia, more than 850 lives lost; 6 March 2012: special service and ceremonies for the 25th anniversary of the Herald’s sinking.

After a commemorative service to be held in the Parish Church of St Mary’s Dover this coming Monday – the exact 30th. anniversary of the sinking – the bell of the Herald of Free Enterprise, hitherto owned by a Belgian national, will be presented to the Port of Dover during a short ceremony in the Parish Hall. Many crew, survivors, and bereaved families will attend.

The country at large – and certainly P&O – but definitely not each survivor, definitely not each shattered, bereaved, relative of those who drowned, has tended to forget the Herald of Free Enterprise. So what do these last 30 years tell us?

Lesson one: For want of a nail

For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

Townsend Thoresen did not even fit the most rudimentary – efficient nonetheless – captain’s alert.

Lesson two: A titular, or holding, company is necessarily responsible for its “brands” – and all its brands’ shortcomings – from the very first day of takeover. In the weeks following the March 1987 disaster, P&O (Herald owners since December 1986) rode two horses: anxious to use Townsend Thoresen badging and documentation when P&O itself might have come into the spotlight; yet keen to use P&O labelling when Townsend Thoresen became too toxic a public sales pitch. Sheen was actually quite forthright in two of his conclusions: the company was “infected with a disease of sloppiness from top to bottom” and its board of directors “did not have any proper comprehension of what their duties were”.

None of this prevented then Prime Minister

Margaret Thatcher bestowing upon her reported friend and exemplar, P&O chairman Sir Jeffrey Sterling (knighted a year before the disaster for “public service and services to industry”) the Baronetcy of Plaistow, and a seat in the House of Lords. A reward for failure ?

Lesson three: It was, and is, in British law, almost impossible to make a charge of corporate manslaughter stick. Long since the Herald prompted Crown prosecutors to attempt to bring the more serious charge – and right up to and including the Glasgow helicopter and bin lorry tragedies of 2013 and 2014 respectively, also the fatal crashing down of Guildford G Live centre’s loading door in 2013 – Crown Court proceedings have consistently failed through “lack of evidence of culpability”, an inability to discover a “guiding mind”. Lastly, many a sympathetic jury acquits plausible defendants – however compelling the case made against them may appear to be.

Lesson four: Public inquiries into disasters such as the Herald must never be rushed. Key Zeebrugge witness Stephen Homewood was heard for fewer than 40 minutes in front of Sheen, then given even less of a platform at the perfunctory inquest. In these days of social media it is easier for survivors and victims’ families to share information and organise, putting them in a potentially stronger position, but this was then not the case. Sheen was too hasty, in common with the far too speedily convened and concluded Popplewell Inquiry into the 1985 Bradford City stadium fire and the original Taylor “Inquiry” into Hillsborough. Only the Fennell Report on the 1987 King’s Cross Underground fire and a decades-later, new, Hillsborough Inquiry attempted a semblance of thoroughness.

Lesson five: We never learn. Years before the Herald sank, one of her class completed her entire Channel crossing with her bow doors open, undiscovered. And two months after the Herald’s capsize, the Daily Mirror reported that P&O was still setting off from port without due safeguards. Ferry crew often remain poorly trained, so much so that even safety exercises designed for them have been botched leading to crew deaths and grave injury. And one dare not speculate on the safety standards of Indonesian, Philippine or Vietnamese ferries.

Lesson six: Good lighting is essential. Boats and aeroplanes alike must have solid, waterproof, fireproof, lighting and walkie-talkies. The 7/7 London Tube and bus atrocities in 2006 showed yet again that emergency lighting, not to mention messaging, was completely insufficient.

Lesson seven: Post-disaster gestures are at once empty and insulting if managements maintain their unchallenged Gentlemen v Players perspective. P&O’s incidental – but deeply hurtful – acts of thoughtlessness after the Herald’s sinking are too numerous to list... but here are a few: Sterling and Townsend Thoresen refusing to speak to certain crew survivors; P&O not paying for travel or subsistence – or even coffee – for those attending the inquiry, inquest and memorials; P&O unprepared to offer crew any compassionate leave at all that was not deducted from their annual leave entitlement; P&O holding private functions and memorials where affected crew were neither invited nor welcome; P&O giving the church a template of a different ship to represent in stained glass; P&O drawing up the wreck of the Herald right next to a complimentary cruise for a few surviving employees and their families (the Herald on its way to being scrapped in Taiwan); P&O sacking most Herald crew in a bitter, but unrelated, conflict with the Seamen’s union; crew and the relatives of crew, dead or alive, marginalised as an inconvenience or embarrassment by their employers; P&O sending mass-produced letters, or none, of appreciation; P&O dumping seemingly spare “medals” through crew letter-boxes; P&O spending almost twice as much on its learned counsel as it was prepared to pay Sheen; P&O not offering to pay the £10 Buckingham Palace pettily charged for each commemorative photograph; P&O’s niggardly, minimal, compensation awards, paid only after a fight... with more tales coming to light.

Illustrative of this mindset, a “final” word might go to Peter Ford, former chairman of Townsend Thoresen, retired and living in London, aged 88, when he made this observation in the 25th anniversary year of 2012: “It was a very difficult situation. Probably the biggest mistake that we made is that we somewhat underestimated the number of people who had been killed, saying it was about 136 when actually it was 193 ... I think we did the right thing to accept responsibility and do our best in what were extremely difficult circumstances, but we didn't get everything right.”

Now over to Wallace Ayers, former technical director of Townsend Thoresen, who took early retirement three weeks after the sinking. Again in 2012, Mr. Ayers, then aged 73 and living in Reigate, was anxious to observe: “It [my criminal trial] was, as far as I'm concerned, a monstrous injustice and a monstrous waste of money. It [the Herald’s sinking] is in the past, but it’s still in the present. The Herald of Free Enterprise was well-built and it was misused. It was just one of those tragic accidents.”

By Godfrey Holmes Friday 3 March 2017

WEALDEN'S

OFFICERS FROM 1983 TO 2018

|

Ian

Kay

Assist.

Dist. Plan.

|

Charles

Lant

Chief

Executive

|

Victorio

Scarpa

Solicitor

|

Timothy

Dowsett

Dist.

Secretary

|

Christine

Nuttall

Solicitor

|

Dr

David Phillips

Enforcement

|

|

Daniel

Goodwin

Chief

Executive

|

J

Douglas Moss

Policy

|

Kelvin

Williams

Dist.

Planning

|

Trevor

Scott

Solicitor

|

David

Whibley

Enforcement

|

Christine

Arnold

Planning

|

|

-

|

Beverley

Boakes

Legal

Secretary

|

Patrick

Coffey

Planning

|

Julian

Black

Planning

|

Ashley

Brown

Dist.

Planning

|

Derek

Holness

Former

CEO

|

Abbott

Trevor - Alcock

Charmain - Ditto - Arnold

Chris (Christine) - Barakchizadeh

Lesley - Paul Barker - Bending

Christopher

Black

Julian - Boakes Beverley - Bradshaw

Clifford - Brigginshaw

Marina - Brown

Ashley - Coffey

Patrick - Douglas

Sheelagh

Dowsett Timothy - Flemming

Mike - Forder Ralph - Garrett

Martyn - Goodwin Daniel

- Henham J - Holness

Derek

Hoy

Thomas - Johnson

Geoff - Kavanagh Geoff - Kay Ian - Kay

I. M.

- Barbara Kingsford - Lant Charles - Mercer

Richard

Mileman Niall - Moon

Craig - Moss Douglas, J. - Nuttall

Christine - Pettigrew Rex - Phillips

David - Scarpa

Victorio - Scott

Trevor

Kevin Stewart -

Turner Claire - Wakeford

Michael. - Whibley David - White,

George - Williams

Kelvin - Wilson Kenneth - White

Steve