|

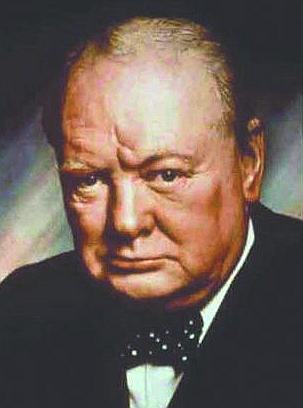

WINSTON CHURCHILL 1874-1965

HOME | CASE STUDIES | HISTORY | LAW | POLITICS | RIGHTS | SITE INDEX

|

"Don't be content with things as they are, the earth is yours and the fullness thereof"

Winston Churchill would turn in his grave if he visited the corruption in planning and so-called law enforcement departments across the country..................

Winston Churchill -

The master statesman stood alone against fascism and

renewed the world's faith in the superiority of democracy.

Sir Winston Churchill

Churchill came of a military dynasty. His ancestor John Churchill had been created first Duke of Marlborough in 1702 for his victories against Louis XIV early in the War of the Spanish Succession. Churchill was born in 1874 in Blenheim Palace, the house built by the nation for Marlborough. As a young man of undistinguished academic accomplishment — he was admitted to Sandhurst after two failed attempts — he entered the army as a cavalry officer.

He took enthusiastically to soldiering (and perhaps even more enthusiastically to regimental polo playing) and between 1895 and 1898 managed to see three campaigns: Spain's struggle in Cuba in 1895, the North-West Frontier campaign in India 1897 and the Sudan campaign of 1898, where he took part in what is often described as the British Army's last cavalry charge, at Omdurman. Even at 24, Churchill was steely: "I never felt the slightest nervousness," he wrote to his mother. "[I] felt as cool as I do now." In Cuba he was present as a war correspondent, and in India and the Sudan he was present both as a war correspondent and as a serving officer. Thus he revealed two other aspects of his character: a literary bent and an interest in public affairs.

The political history of the 20th century can be written as the biographies of six men: Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mao Zedong, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill. The first four were totalitarians who made or used revolutions to create monstrous dictatorships.

Roosevelt and Churchill differed from them in being democrats. And Churchill differed from Roosevelt - while both were war leaders, Churchill was uniquely stirred by the challenge of war and found his fulfillment in leading the democracies to victory.

Winston

Churchill - The master statesman stood

alone against fascism and renewed the world's faith in the superiority of

democracy. Winston Spencer Churchill, probably the most well known person in English history, once went to school in Brighton. This is what Churchill himself tells us in his book "My Early Life" first published in 1930. However, although close to the truth, Churchill actually went to school in neighbouring Hove.

Churchill came of a military dynasty. His ancestor John Churchill had been created first Duke of Marlborough in 1702 for his victories against Louis XIV early in the War of the Spanish Succession. Churchill was born in 1874 in Blenheim Palace, the house built by the nation for Marlborough. As a young man of undistinguished academic accomplishment — he was admitted to Sandhurst after two failed attempts - he entered the army as a cavalry officer.

He took enthusiastically to soldiering (and perhaps even more enthusiastically to regimental polo playing) and between 1895 and 1898 managed to see three campaigns: Spain's struggle in Cuba in 1895, the North-West Frontier campaign in India 1897 and the Sudan campaign of 1898, where he took part in what is often described as the British Army's last cavalry charge, at Omdurman. Even at 24, Churchill was steely: "I never felt the slightest nervousness," he wrote to his mother. "[I] felt as cool as I do now." In Cuba he was present as a war correspondent, and in India and the Sudan he was present both as a war correspondent and as a serving officer. Thus he revealed two other aspects of his character: a literary bent and an interest in public affairs.

"Don't be content with things as they are, the earth is yours and the fullness thereof"

The British statesman Winston Churchill was a prolific writer throughout his life, and during his periods out of office regarded himself as a professional writer who was also a Member of Parliament. Despite his aristocratic birth, he inherited little money (his mother spent most of his inheritance) and always needed ready cash to maintain his lavish lifestyle. Some of his historical works, such as A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, were written primarily to raise money.

Although Churchill was an excellent writer, he was not a trained historian, and his historical works show many limitations. In his youth he was an avid reader of history, but within a narrow range. The major influences on his historical thought, and his prose style, were Clarendon's history of the English Civil War, Gibbon's Decline and Fall and Macaulay's History of England. He had no knowledge of, or interest in, social or economic history, and he always saw history as essentially political and military, driven by great men rather than by economic forces or social change.

Churchill was one of the last (and most influential) exponents of "Whig history" — the ideology of the 18th and 19th century Whigs that the British people had a unique greatness and an imperial destiny and that all British history should be seen as progress towards fulfilling that destiny. This belief inspired his political career as well as his historical writing. It was an old-fashioned view of history even in Churchill's youth, but he never modified it or showed any interest in other schools of history. Although he employed professional historians as assistants on his major works, they had no influence over the content of his works.

Winston Churchill in military uniform 1896

Churchill's historical works fall into three categories. The first is works of family history, the biographies of his father, Life of Lord Randolph Churchill (1906), and of his great ancestor, Marlborough: His Life and Times (four volumes, 1933–38). These are still regarded as fine biographies, but are marred by Churchill's desire to present his subjects in the best possible light. He made only limited use of the available source materials, and in the case of his father suppressed much material from family archives that reflected badly on Lord Randolph. The Marlborough biography shows to the full Churchill's great talent for military history. Both books have been superseded by more scholarly works, but are still highly readable.

The second category is Churchill's autobiographical works, including his early journalistic compilations The Story of the Malakand Field Force (1898), The River War (1899), London to Ladysmith via Pretoria (1900) and Ian Hamilton's March (1900). These latter two were issued in a re-edited form as My Early Life (1930). All these books are colourful and entertaining, and contain some valuable information about Britain's imperial wars in India, Sudan and South Africa, but they are essentially exercises in self-promotion, since Churchill was already a Parliamentary candidate in 1900.

Churchill's reputation as a writer, however, rests on the third category, his three massive multi-volume works of narrative history. These are his histories of the First World War — The World Crisis (six volumes, 1923–31), and of The Second World War (six volumes, 1948–53), and his History of the English-Speaking Peoples (four volumes, 1956–58, much of which had been written as journalism in the 1930s). These are among the longest works of history ever published (The Second World War runs to more than two million words), and earned him the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Churchill's histories of the two world wars are, of course, far from being conventional historical works, since the author was a central particpant in both stories and took full advantage of that fact in writing his books. Both are in a sense therefore memoirs as well as histories, but Churchill was careful to broaden their scope to include events in which he played no part — the war between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, for example. Inevitably, however, Churchill placed Britain, and therefore himself, at the centre of his narrative. Arthur Balfour described The World Crisis as "Winston's brilliant autobiography, disguised as a history of the universe." In any case he had far fewer documentary sources for matters not involving Britain.

Winston Churchill 'V for victory' salute world war II

As a Cabinet minister for part of the First World War and as Prime Minister for nearly all of the Second, Churchill had unique access to official documents, military plans, official secrets and correspondence between world leaders. After the First War, when there were few rules governing these documents, Churchill simply took many of them with him when he left office, and used them freely in his books — as did other wartime politicians such as David Lloyd George. As a result of this, strict rules were put in place preventing Cabinet ministers using official documents for writing history or memoirs once they left office.

The World Crisis began as a response to Lord Esher's attack on his reputation in his memoirs, but it soon broadened out into a general multi-volume history. The volumes are a mix of military history, written with Churchill's usual narrative flair; diplomatic and political history, largely written to justify Churchill's own actions and policies during the war; portraits of other political and military figures, usually written to further political vendettas or settle debts (most notably with Lloyd George), and personal memoir, written in a colourful but highly selective manner. Today these books are of less value as historical references than as biographical or literary ones. As with all Churchill's works, they have nothing to say about economic or social history, and are colured by his political views — particularly in regards to the Russian Revolution of 1917. But they remain highly readable for their narrative skill and vivid portrayals of people and events.

When he resumed office in 1939, Churchill fully intended writing a history of the war then beginning. He said several times: "I will leave judgements on this matter to history — but I will be one of the historians." To circumvent the rules against the use of official documents, he took the precaution throughout the war of having a weekly summary of correspondence, minutes, memoranda and other documents printed in galleys and headed "Prime Minister's personal minutes." These were then stored at his home for future use. As well, Churchill actually wrote or dictated a number of letters and memorandums with the specific intention of placing his views on the record for later use as a historian.

Winston Churchill portrait

This all became a source of great controversy when The Second World War began appearing in 1948. Churchill was not an academic historian, he was a politician, and was in fact Leader of the Opposition, still intending to return to office. By what right, it was asked, did he have access to Cabinet, military and diplomatic records which were denied to other historians?

What was unknown at the time was the fact that Churchill had done a deal with the Attlee Labour government which came to office in 1945. Recognising Churchill's enormous prestige, Attlee agreed to allow him (or rather his research assistants) free access to all documents, provided that (a) no official secrets were revealed (b) the documents were not used for party political purposes and (c) the typescript was vetted by the Cabinet Secretary, Sir Norman Brook. Brook took a close interest in the books and rewrote some sections himself to ensure that nothing was said which might harm British interests or embarrass the government. Churchill's history thus became a semi-official one.

Churchill's privileged access to documents and his unrivalled personal knowledge gave him an advantage over all other historians of the Second World War for many years. The books had enormous sales in both Britain and the United States and made Churchill a rich man for the first time. It was not until after his death and the opening of the archives that some of the deficiencies of his work became apparent.

Some of these were inherent in the difficult position Churchill occupied as a former Prime Minister and a serving politician. He could not reveal military secrets, such as the work of the code-breakers at Bletchley Park, or the planning of the atomic bomb. He could not discuss wartime disputes with figures such as Dwight Eisenhower, Charles de Gaulle or Tito, since they were still world leaders at the time he was writing. He could not discuss Cabinet disputes with Labour leaders such as Attlee, whose goodwill the project depended on. He could not reflect on the deficiencies of generals such as Archibald Wavell or Claude Auchinleck, for fear they might sue him (some indeed threatened to do so).

Other deficiencies were of Churchill's own making. Although he mentioned the fighting on the Eastern Front, he had little real interest in it and no access to Soviet or German documents, so his account is a pastiche of secondary sources, largely written by his assistants. The same is true to some extent of the war in the Pacific, except for episodes such as the fall of Singapore in which he was involved. His account is based heavily on his own documents, so it greatly exaggerates his own role. Although he was of course a central figure in the war, he was not as central as his books suggest, particularly after 1943. Although he is usually fair, some personal vendettas are aired — against Stafford Cripps, for example.

Sir Winston Churchill

The Second World War can still be read with great profit by students of the period, provided it is seen mainly as a memoir by a leading participant rather than as an authoritative history by a professional and detached historian. The Second World War, particularly the period between 1940 and 1942 when Britain was fighting almost alone, was after all the climax of Churchill's career and his personal account of the inside story of those days is unique and invaluable. But since the archives have been opened far more accurate and reliable histories have been written.

Churchill's History of the English-Speaking Peoples was commissioned and largely written in the 1930s when Churchill badly needed money, but it was put aside when war broke out in 1939, being finally issued after he left office for the last time in 1955. Although it contains much fine writing, it shows Churchill's deficiencies as a historian at their most glaring. It is generally regarded as ponderous, tendentious and very old-fashioned, seeing world history as a one-dimensional pageant of battles and speeches, kings and statesmen, in which the English occupy central stage. Events of central importance to modern history, such as the industrial revolution, are scarcely mentioned. Although Churchill's enormous prestige ensured that the books were respectfully received and sold well, they are now little read.

H.G. Wells- who, it should be said, was a staunch Socialist and greatly disliked Churchill for his capitalist views - included in his book The Shape of Things to Come (1933) a passage referring to Churchill's history writing, presented as an extract from a fictional history book written in 2106:

Sir Winston was defeated however during the 1945 election by the Labour party who ruled until 1951. Churchill at the age of 77 regained his power in 1951 and lead Britain once again until 5th April 1955 when ill health forced him to resign. The news was announced in a statement from Buckingham Palace, It said: "The Right Honourable Sir Winston Churchill had an audience with the Queen this evening and tendered his resignation as Prime Minister and First Lord of the Treasury, which Her Majesty was graciously pleased to accept." Sir Winston Churchill's resignation followed a dinner party held at 10 Downing Street the night before, which was attended by the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh as well as a number of the prime minister's past and present government colleagues. Tributes to the 81-year-old premier, who will be replaced by Sir Anthony Eden tomorrow, have poured in from around the world.

On the 24th of April 1953 Winston Churchill was made a Knight of the Order of the Garter in recognition of his services to his country.

He spent much of his latter years writing, and painting. Churchill was a gifted amateur painter, and wrote Painting as a Pastime in 1948. His works numbered over 500, are of remarkable quality and have received the most positive criticism in the English press.

Sir Winston Churchill, Airedale Terrier and Land Rover

In 1963, pursuant to an Act of Congress, U.S. President John F. Kennedy named Churchill the first Honorary Citizen of the United States. Churchill was too ill to attend the White House ceremony, so his son and grandson accepted the award for him.

On January 15 1965 Churchill suffered another stroke, a severe cerebral thrombosis, that left him gravely ill. Sadly on the 24th January 1965 Sir Winston Churchill died in his London home at Hyde Park Gate, he left a wife and three children. His eldest daughter, Diana, had committed suicide in 1963 and another daughter died in infancy.. Earlier in his illness, there had been crowds anxiously waiting for news at the top of the quiet Kensington cul-de-sac - but when the announcement finally came there was only a handful of journalists in the street.

An official announcement went across the world from 10 Downing Street at 8:55am in a message from the Prime Minister, Mr. Harold Wilson. "It is with great regret that I have heard of the death of Sir Winston Churchill. He will be mourned all over the world by all who owe so much to him. He is now at peace after a life in which he created history and which will be remembered as long as history is read. Our thoughts and sympathy are with his family." Within half-an-hour, crowds began to gather near his home to pay homage to Britain's greatest wartime leader.

Sir Winston had spent the past few days lying in the downstairs room he converted to a bedroom after a fall four years ago in which he injured his back. Members of the family were summoned to his bedside at 7am. Lady Churchill and the couple's eldest surviving daughter, Mary Soames, had been with him throughout his illness. Their son, Randolph Churchill was seen arriving with his son, Winston. Soon after, Sir Winston's actress daughter, Lady Sarah Audley, looking pale and drawn, arrived with her daughter, Celia Sandys.

Following his death Sir Winston's body lay in state in Westminster, an honour not accorded any English statesman since Gladstone in 1898. In the middle of the Hall was garnet-coloured carpet. Raising from it was the platform on which stood the catafalque, 7ft. high. The bier was covered in black velvet with edging of silver braid and on it, the coffin, draped with the Union Flag. Sir Winston’s insignia as a Knight of the Garter – collar, star and garter were placed on a black velvet cushion on the coffin. A golden cross stood at the head, four large candles glowed at the corners of the bier

The

lying-in-state commenced 9:00am, Wednesday, January

27th.For three days, twenty-three hours a day, the public filed past the

body of Sir Winston Churchill lying-in-state in Westminster Hall. People

queued, most for three or four hours, to pay homage to their statesman. A

total of 321,360 people filed past the catafalque during the three days of

lying-in-state.

Winston

Churchill's

statue in London SIR

WINSTON'S BEST QUOTES We

make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give. There

is no such thing as a good tax. Some

see private enterprise as a predatory target to be shot, others as a

cow to be milked, but few are those who see it as a sturdy horse

pulling the wagon. The

inherent vice of capitalism is the unequal sharing of blessings; the

inherent virtue of socialism is the equal sharing of miseries. We

contend that for a nation to tax itself into prosperity is like a man

standing in a bucket and trying to lift himself up by the handle. An

appeaser is one who feeds a crocodile—hoping it will eat him last. The

problems of victory are more agreeable than the problems of defeat,

but they are no less difficult. From

now on, ending a sentence with a preposition is something up with

which I shall not put. A

fanatic is one who can’t change his mind and won’t change the

subject. Bessie

Braddock: “Sir, you are drunk.” Nancy

Astor: “Sir, if you were my husband, I would give you poison.” A

lie gets halfway around the world before the truth has a chance to get

its pants on. Once

in a while you will stumble upon the truth but most of us manage to

pick ourselves up and hurry along as if nothing had happened. If

you are going to go through hell, keep going. It

is a good thing for an uneducated man to read books of quotations. You

have enemies? Good. That means you’ve stood up for something,

sometime in your life. If

you have ten thousand regulations, you destroy all respect for the

law. You

can always count on Americans

to do the right thing—after they’ve tried everything else. History

will be kind to me for I intend to write it. Writing

a book is an adventure. To begin with, it is a toy and an amusement;

then it becomes a mistress, and then it becomes a master, and then a

tyrant. The last phase is that just as you are about to be reconciled

to your servitude, you kill the monster, and fling him out to the

public. The

farther backward you can look, the farther forward you are likely to

see. A

sheep in sheep’s clothing. (On Clement Atlee) A

modest man, who has much to be modest about. (On Clement Atlee) I

am ready to meet my Maker. Whether my Maker is prepared for the ordeal

of meeting me is another matter. The

truth is incontrovertible, malice may attack it, ignorance may deride

it, but in the end; there it is. A

pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity; an optimist sees

the opportunity in every difficulty. To

improve is to change; to be perfect is to change often. Politics

is the ability to foretell what is going to happen tomorrow, next

week, next month and next year. And to have the ability afterwards to

explain why it didn’t happen. Socialism

is a philosophy of failure, the creed of ignorance, and the gospel of

envy. Solitary

trees, if they grow at all, grow strong. Success

consists of going from failure to failure without loss of enthusiasm. The

best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the

average voter. It

has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except

all the others that have been tried. Everyone

has his day and some days last longer than others. The

whole history of the world is summed up in the fact that, when nations

are strong, they are not always just, and when they wish to be just,

they are no longer strong. From

Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has

descended across the Continent. “The

Sinews of Peace” speech, Westminster College, Fulton, Missouri, March 5,

1945: If

Hitler invaded hell I would make at least a favorable reference to the

devil in the House of Commons. Those

who can win a war well can rarely make a good peace and those who

could make a good peace would never have won the war. Courage

is the first of human qualities because it is the quality that

guarantees all the others. The

problems of victory are more agreeable than those of defeat, but they

are no less difficult. If

you will not fight for right when you can easily win without blood

shed; if you will not fight when your victory is sure and not too

costly; you may come to the moment when you will have to fight with

all the odds against you and only a precarious chance of survival.

There may even be a worse case. You may have to fight when there is no

hope of victory, because it is better to perish than to live as

slaves. You

ask, What is our policy? I will say; “It is to wage war, by sea,

land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God

can give us: to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed

in the dark lamentable catalogue of human crime. That is our

policy.” You ask, What is our aim? I can answer with one word:

Victory—victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror,

victory however long and hard the road may be; for without victory

there is no survival. We

shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in

France, we shall fight on the seas and the oceans, we shall fight with

growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend

our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches,

we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields

and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never

surrender Hitler

knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war.

If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be free and life of the

world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands. But if we fall,

then the whole world, including the United States, including all

that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new

Dark Age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the

lights of perverted science.

Let us therefore brace ourselves to

our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and

its Commonwealth lasts for a thousand years, men will still say, “This

was their finest hour!”

The

State Funeral of Sir Winston Churchill 1965 LINKS

and REFERENCE Churchill,

Winston (1948–1953), The Second World War, 6 vols. Gilbert,

Martin (1995). Second World War, Phoenix. ISBN 1857993462. Keegan,

John (1989). The Second World War, Hutchinson. ISBN 0091740118. Liddel

Hart, Sir Basil (1970). History of the Second World War,

London: Cassell. ISBN 0304935646. Murray,

Williamson and Millett, Allan R. (2000). A War to Be Won: Fighting

the Second World War, Harvard University Press. ISBN 067400163X. Overy,

Richard (1995). Why the Allies Won, Pimlico. ISBN 0712674535. Shirer,

William L. (1959). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, Simon

& Schuster. ISBN 0671624202. Smith,

J. Douglas and Richard Jensen. World War II on the Web: A Guide to

the Very Best Sites (2002) Weinberg,

Gerhard L. (1994). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War

II, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521443172. LINKS

& REFERENCE Amnesty

International War

Criminals, Executions Battle

of Britian

Calendar

Aircraft

Links

Commanders

David

Ben-Gurion

General Deutsche

Welle special section on World War II created

by one of Germany's public broadcasters on World War II and the world

60 years after. Halford

Mackinder's Necessary War An essay describing the geopolitical aspects

of World War II Haagse

Bunker Ploeg : Photo site about the Atlantikwall in the

Netherlands . Media Multimedia

map -

Presentation that covers the war from the invasion of Russia to the

fall of Berlin Thousands

of World War II Photographs & Movies - Free to download Virtual

Museum of World War II -

interesting pictures & info Winston

and

Clementine Churchill's grave Stories WW2

People's War -

A project by the BBC

to gather the stories of ordinary people from World War II WWII,

divisive memories (en) -

from an online issue from www.cafebabel.com Workers'

War: Home Front Recalled -

A project by London Metropolitan University, TUC and the National

Pensioners Convention to document the history of workers during World

War II Remembering

Our Allied Veterans of WWII Stories

from Allied and Anti-fascist Vets including Spanish Civil War Specific WWII

US women's service organizations —

History and uniforms in color (WAAC/WAC, WAVES, ANC, NNC, USMCWR, PHS,

SPARS, ARC and WASP) Veterans

Of The US Armed Forces Services,

information, resources, and image gallery for veterans of the United

States Armed Forces. Front

page of the 6 June, 1944 edition of

The

New York Times. Using

Historical Statistics To Teach about World War II. ERIC Digest. Speech

delivered by premier Benito Mussolini (Rome, Italy, February 23, 1941) Daily

reports -

Extremely detailed daily action reports from the German side Juno

Beach - An

indepth examination of one of Canada's

greatest WWII contributions: Juno Beach.

Portrait

of Sir Winston Churchill - the British Bulldog GENERAL

HISTORY

MARITIME

HISTORY FIRST

SOLAR PACIFIC NAVIGATION HMS

ENDURANCE

Battle

of Britian Calendar

Aircraft

Links

Commanders

Units

& stations Gallery BACK

TO BATTLE OF BRITAIN PAGE |

|

|

This website is Copyright © 1999 & 2018 HST. All rights reserved. Max Energy Limited is an educational charity.

|